Wealth Management: Market Perspective – Normal service resumes

Risk as a fact of investment life

'October: This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.' - Mark Twain

Stock markets had been remarkably calm

Mark Twain's 'peculiarly dangerous months' have actually been few and far between of late. For much of the decade following the Global Financial Crisis, even as pundits proclaimed the imminent end of the world for all sorts of exciting and ingenious reasons, global capital markets were largely docile, quietly delivering some of the best sustained returns on record.

Since 2016, the lack of volatility itself became remarkable. Collectively, investors and advisers have perhaps needed reminding that markets can be noisy, and go down as well as up.

The latest reminder came in October. Most big stock market indices, and most sectors, fell markedly. The all-countries index fell by roughly 10% from its September peak.

Oil prices also fell sharply, but other commodity prices were more resilient. Most government bonds, gold and the yen - 'safe-haven' assets - rallied, but modestly. The US 10-year Treasury note yield has remained above 3%.

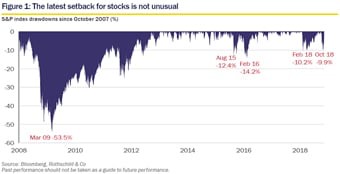

That recent stability aside, this latest stock market setback does not look unusual. There have been perhaps half a dozen similar episodes since 2009.

Click the image to enlarge

The jury is out on what caused it - if anything did, that is: we should be wary of over-analysis.

There are plenty of things to worry about…

Analysts who quickly tell us not to worry may be missing the point. There is always something to worry about. The very open-endedness that makes stocks good long-term investments can go scarily into reverse.

History shows that economic storms sometimes break from a seemingly clear sky. Corporate profits can evaporate with little warning. Big financial institutions can disappear. As investors in stocks, we own businesses, and face these unavoidable - and innumerable - risks. And as they say, the stock market indices go up on the escalator, but come down in the elevator. It is not possible to offer convincing reassurance.

Familiar market threats might include:

- Disappointing corporate profits, whether in isolation or because of:

- an autonomouse economic downturn

- tighter monetary or fiscal policy, leading to slowdown

- big trade protection, or a supply-driven surge in oil prices

- Reckless borrowing - by Italy, Chinese corporates, or US home-buyers - leading to financial crisis, risk aversion and poor profits.

- Geopolitical stress and uncertainty - triggered by US insensitivity, Brexit or North Korea - which causes a flight to safe-haven assets.

- Excessive valuations

… but they have not suddenly got worse

The market could be seeing something early - but as noted above, it doesn't always do that. The US economist James Tobin famously quipped that “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions”.

As yet, although business surveys are cooling (page 6), the next US recession still seems some way off. The Fed is in tightening mode, and likely to remain so, but US interest rates and bond yields are still historically subdued. Corporate results are robust - some high-profile misses notwithstanding. There have been no new escalations in political uncertainty of the sort that might affect markets.

For sure, US tariffs, Italy's budget and Brexit are all real concerns, but they have not become more pressing, and bad outcomes are far from guaranteed. Most recently, the US mid-term election results were widely expected.

With President Macron's reforms losing momentum, Chancellor Merkel's confirmation that she will not seek re-election in 2021 may rekindle scepticism regarding the leadership of the EU project. It feels like a background concern for now, however.

Meanwhile, the big picture remains one of healthy profitability alongside only gradual monetary normalisation. And as we note below, valuations have not been alarming.

The broadness of stocks' decline, and the failure of safe-haven assets to rally more substantially, hints perhaps at profit-taking by institutional investors - as in early 2016, maybe - rather than a more sinister macro cause.

Unknown unknowns?

In trying to see into the future, we are often unwitting prisoners of the past. All sorts of unprecedented and unimagined risks may be lurking ahead.

We can only keep an open mind, and hold some portfolio insurance. Some risks are simply uninsurable, the financial equivalent of an asteroid strike perhaps. For insurance to pay out, our insurers need to survive.

What next?

We do worry about a 'second derivative' effect: strong US growth and tax cuts have created such a boom for business in 2018 that it feels as if things are as good as they can possibly get.

A big profit slowdown in 2019 is possibly inevitable - alongside rising US interest rates - and this could lead to the earnings disappointment featured on our list. Is realisation dawning now?

If so, it may be a bearable burden for long-term investors. The likely level of earnings at which the inevitable slowdown will occur may yet be higher than expected. And slower growth, rather than an outright fall, will leave most valuation metrics intact.

We are not (we hope) gullible enough to believe in 'permanently high' plateaus. But we thought stocks were good long-term value before this slide, and think they still offer the best chance of inflation-beating returns for long-term investors.

Click here to continue: Market Perspective - Are stocks too dear? >

In this Market Perspective:

Foreword

Normal service resumes (current page)

Are stocks too dear?

Economy and markets: background

Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (3.9 MB)