Wealth Management: Market Perspective – Normal service resumes: Are stocks too dear?

'Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing' - Oscar Wilde

Valuing stocks is not easy, and history can be cruel. Financial broadsheets and central bank commentaries have casually asserted that stocks are dear for several decades. Growth investors' models collapsed with government bond yields. Value investors thought they had Mozart's perfect pitch.

The clue is the word 'market'. Prices are ultimately decided subjectively: if there are no buyers, prices collapse. If there are no sellers, they soar.

We seek objectivity by comparing prices to earnings, book values, discount rates and the like, but those move around a lot. Even if they didn't, the way we view them would.

When we suggest stocks are cheap or dear, we are expressing an opinion. Nowhere is financial precision more spurious than in the realm of valuation. There are no absolutes - no perfect pitch.

So what can we usefully say about stock valuations? Did October's setback happen because they were just too dear?

We think not. We try to keep an open mind, but we want our metrics to cover the whole market, not just some countries and sectors (or median companies) and to use credible data (which rules out 100-year comparisons).

The main reason we want to invest in stocks - to own businesses - is a wish to share in economic growth. If we're going to argue that stocks are good value, we have to be able to see some sort of link, however loose, to that growth. Most long-term gains in stock prices are traceable to corporate earnings.

Click the image to enlarge

Momentum-based indicators

One minimalist approach simply compares stock prices with their trends. This is arguably not really a “valuation” per se, but if traders base their decisions on a stock index falling below (say) its 200-day moving average, it might prove self-fulfilling. We do not use these often - they are short term in focus, and ignore that growth.

Flow-based measures

The most common approaches compare prices with measures of income such as earnings, dividends, cashflow, sales or earnings before interest, tax and depreciation (EBITDA).

PE ratios - prices divided by earnings - can be viewed as the number of years of earnings your investment costs. Alternatively, they can be turned upside down, and seen as yields (which is how we usually view dividends).

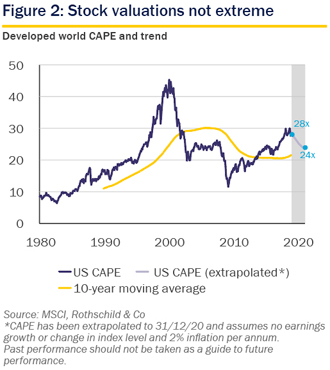

Earnings are volatile. Profits are cyclical, and balance sheet write-downs can be big (see 2008 in figure 2). 'Cyclically adjusted' PE (CAPE) ratios use a 10-year moving average (often in real terms) to smooth earnings. But US earnings fell so sharply in 2008/9 that they affected the 10-year averages. As that fall drops out, the CAPE denominator will likely continue to grow - and valuations fall - for a while even if earnings now stagnate.

Price/sales and price/EBITDA ratios have become more popular, but are not useful for financial companies, a big sector.

Balance sheet-based measures

Usually, shareholders' funds or 'book values' are relatively stable - two high-profile exceptions being banks in 2008, and telecoms and media companies in 2002 - and so provide another useful valuation benchmark.

Debt or leverage ratios are also often used, but again the data can be difficult to interpret in the case of banks.

'Tobin's Q' compares stock prices to companies' alleged replacement values. It is supposed to be an absolute measure, but data are poor and hard to get, and the idea itself is misconceived.

Discounted cashflow (DCF) approaches

These use a riskless discount rate - usually government bond yields - often adjusted to take into account stocks' greater risk.

In their simplest form, they compare stocks' yield to that on bonds: the so-called 'Fed model' was based on the observation that for much of the '80s and '90s the two yields moved together.

More complex versions can in theory be used to construct absolute valuations - showing not just whether valuations are high or low relative to the past, but whether they are 'fair' or not. In reality, conclusions are hugely sensitive to small changes in input assumptions.

Conclusions

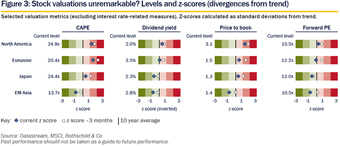

A few of the many valuation metrics that we watch most closely are summarised in figure 3.

Click the image to enlarge

We do not include discounted cash flow-type measures here, though we routinely show stock and bond yields for reference on page 6. Bond yields have been so unusually low of late that such measures would probably have been too lenient.

Generally, most metrics before the sell-off were firmly above 10-year trends. The divergence was not unprecedented or alarming, however, and in a benign economic climate - in contrast to, say, the 1970s and early 1980s, when those trends were lower and 'normalised' interest rates much higher - deserved the benefit of the doubt (remember, this is not a precise exercise).

Valuations now are closer to those trends. Wherever markets go next, we doubt that they will be doing so for valuation-related reasons.

Investment conclusions

Our top-down views are unchanged. Our portfolio managers have been holding some specific protection in anticipation of volatile stock markets, but we have been wary of a more defensive restructuring that could leave us stranded if markets rally. The economic climate remains constructive, and stock valuations are close to trend again. US tax cuts and growth have added some real headroom in 2018; interest rate risk remains modest; and geopolitical risks may be manageable. Stocks can still deliver inflation-beating long-term returns.

- Inflation-adjusted, long-term US Treasury yields still looked low even after their recent rise. Other government bond markets remain still more expensive - most nominal yields remain below likely inflation rates. We still prefer high-quality corporate bonds to government bonds, but they are also expensive. The room for outperformance is falling - most visibly in the eurozone, where the European Central Bank's (ECB) buying will shortly cease and local credit concerns pose some limited risk to banks. We continue to view most bonds and cash currently as portfolio insurance.

- In the eurozone and UK, we continue to favour relatively low duration bonds. In the US we have been more neutral, and see some attraction in inflation-indexed bonds. Speculative-grade credit has run out of longer-term headroom - net of likely default and loss, returns may struggle to match inflation. We are not tempted to add emerging market bonds to multi-asset portfolios, even after their recent sell-off.

- We continue to prefer stocks to bonds in most places, even the UK (where the big indices are in any case driven by global trends). We have few regional convictions - though we think that emerging Asia's structural appeal remains intact, recent trade tension and volatility notwithstanding - and continue to favour a mix of cyclical and secular growth over more defensive bond-like sectors.

Trading currencies does not systematically add value, and there are currently few obvious misalignments among the majors. Cyclical momentum and interest rate carry clearly favour the dollar, but it still has yet to break out of its recent trading range. The pound remains hostage to Brexit tensions, but the domestic policy mix continues to shift in its favour and it is competitive. Higher ECB rates remain some way off, and there are some local credit risks (Italy and Turkey-related bank stresses), but quantitative easing at least is almost finished, the euro is inexpensive and we remain sceptical of the euro disaster scenario. China's monetary policy has loosened preemptively, and the yuan has fallen back towards trend, but on a long-term purchasing power parity (PPP) basis it was highly competitive to begin with, and is now even more so. The yen is cheap, but its monetary policy remains the loosest. We still single out only the Swiss franc among the big currencies: we think its revived safe haven appeal will fade, and it remains expensive on a PPP basis. But the local economy appears in (even) better shape than we'd realised, and if this starts to matter the franc may yet stay stronger for longer.

Click here to continue: Market Perspective - Economy and Markets: background >

In this Market Perspective:

-

Foreword

-

Normal service resumes

-

Are stocks too dear? (current page)

-

Economy and markets: background

-

Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (3.9 MB)