Private debt as an alternative to bank financing

From a timely solution to a must-have instrument

Private debt made its début in the 2000s as a way to meet financing needs, sitting midway between Senior debt (bank loans backed by collateral) and shareholders’ equity (stocks). Use of private debt took off in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, as banks had significantly restricted their lending, particularly to SMEs and companies presenting substantial leverage. Banking regulations had grown stricter, calling for increasingly greater capital adequacy to carry out investments. This made funding for private-sector companies highly detrimental for banks in terms of cost of capital. With investors seeking diversification and returns, and bank disintermediation shrinking the supply of traditional financing solutions, private debt came on to the scene with funding from private-sector institutions (insurers and debt funds).

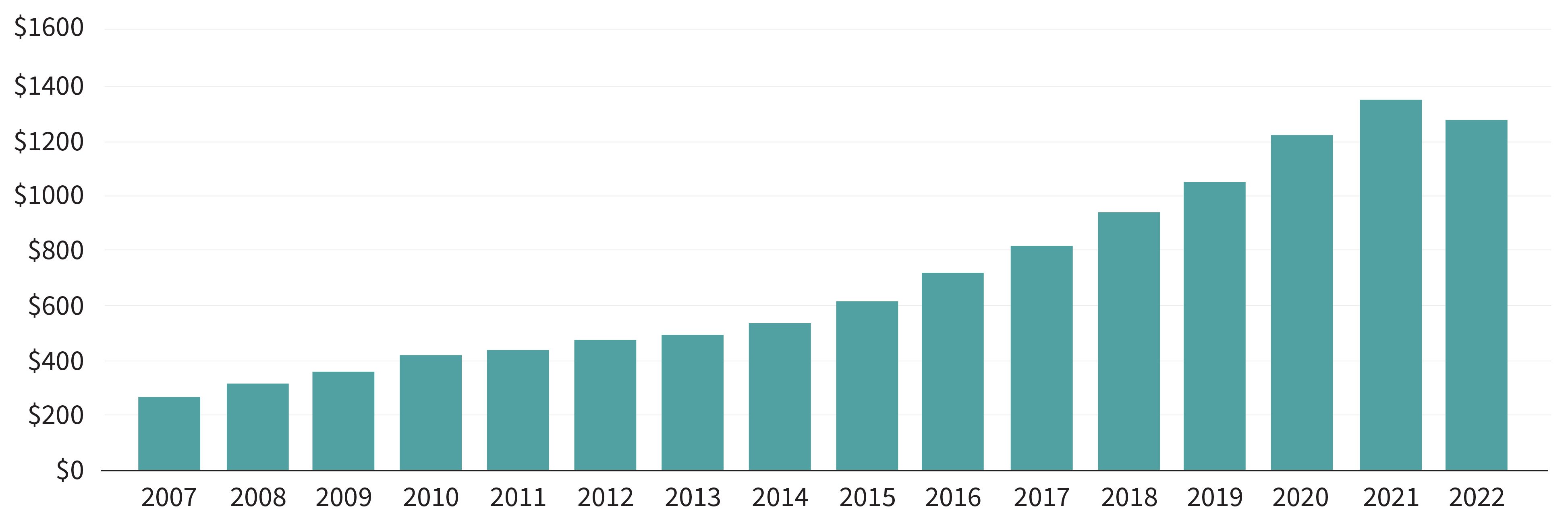

Today, private debt has become a must-have alternative to bank loans for intermediate-size companies, and especially those interested in consolidating their market position and needing to use their cash to fund acquisitions. As such, it is an instrument that meets the needs of borrowers and investors alike, thus spurring its rapid growth. The private debt market has expanded continuously since inception, with AuM having tripled over the last decade (see chart below).

Change in private debt AuM

(in $ bn)

Source Pitchbook – 31/12/2022

Financing structure

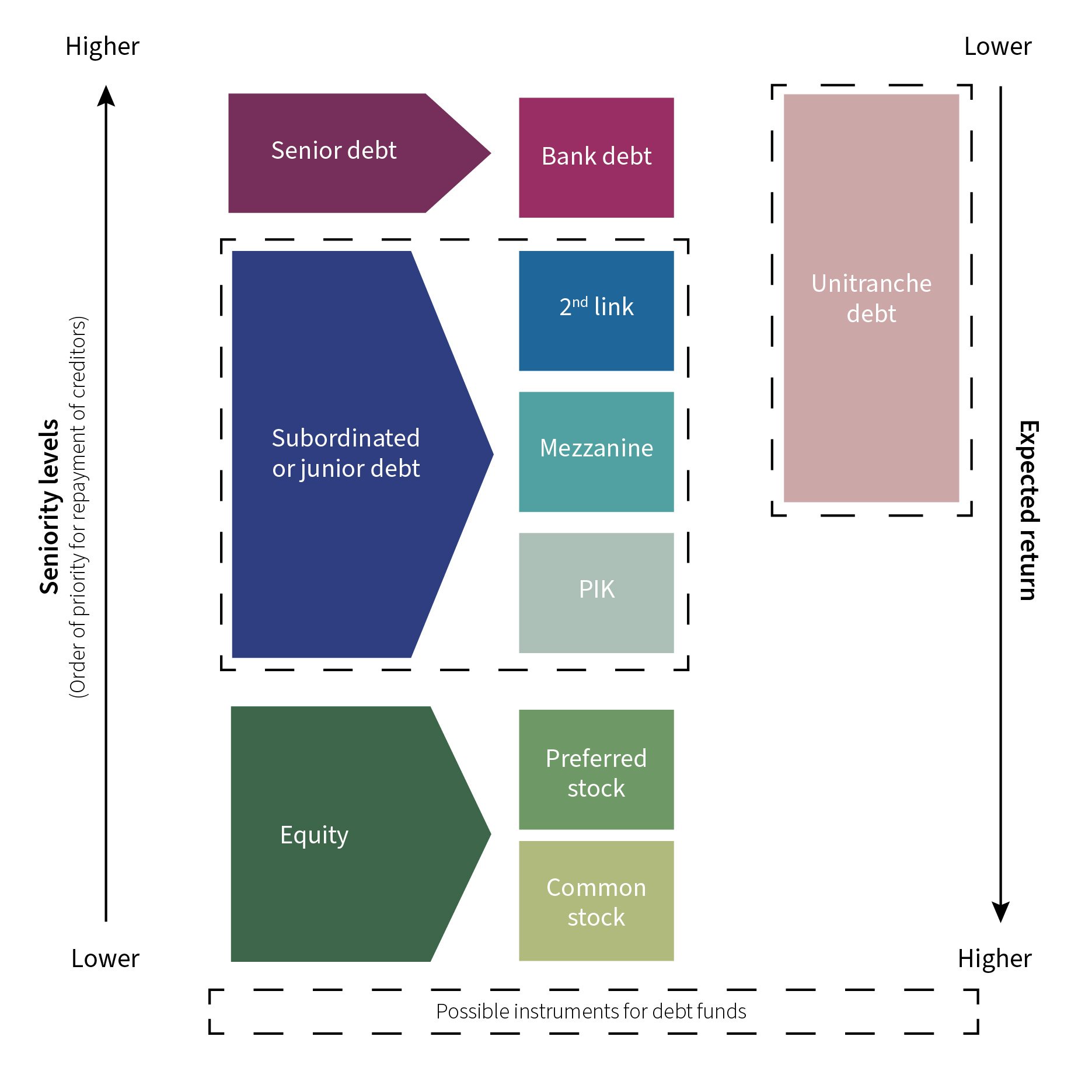

In general, the term private debt refers to “unitranche” senior debt as well as subordinated or junior debt.

The development of this asset class saw the advent of two types of diversified financing, further divided into sub-categories based on level of risk, associated collateral and term (see diagram below).

Senior debt, which generally covers bank loans, is distinguished by its priority in terms of repayment and is associated with top-tier collateral.

Subordinated or junior debt lies midway between senior debt and capital, backed by second-tier collateral, and is repaid after senior debt. It is thus higher-risk than senior debt and pays out a higher return. It is senior, however, to any capital instrument.

2012 is when “single-tranche” loans, also known as unitranche, came along with the purpose of replacing a junior/senior debt combo and allowing companies - most of the time - to deal with a single lender instead of a pool of creditors, and thus build up very close relations with that lender. The borrowing company also gains flexibility and speed of execution. It is a type of senior debt with top-tier collateral, subject to bespoke contracts with flexible repayment terms. The cost of this debt is also higher than a conventional bank loan, but lower than junior debt, as it is less risky. For the lender, this single-tranche debt offers the same security as an investment in senior debt, but with a little more yield because it can reach higher levels of leverage, largely because it is a bullet loan[1].

An asset class in its own right

The highly specific features offered by private debt put it in a class of its own.

First, it should be noted that private debt is, by nature, unlisted and thus not subject to volatility, offering investors the opportunity to enjoy an illiquidity premium and thus a potential higher return compared to traditional listed bonds.

For a Private Debt fund, as compared to Private Equity, the investment period is shorter, i.e. 2 to 3 years on average (versus 3 to 5 years for Private Equity) as is the holding period (2 to 3 years versus 4 to 6 years). Second, since private debt is ranked higher in the capital structure than equities (see diagram above), investors are exposed to less risk should the borrower default.

Private debt funds pay out returns. In most cases, barring a credit event, this instrument offers predictable cash flows in the form of regularly scheduled coupon payments. These payments are usually made quarterly over the life of the transaction, i.e. 6 to 8 years, representing the life of a private debt fund, providing consistency and the ability to produce current yield over very extensive periods.

The debt issued also tends to be variable-rate, which is good for the lender (and thus the investor) in today’s environment of high interbank rates.

A new market environment

The war in Ukraine, climbing inflation and rapid rise of interest rates put a damper on a particularly dynamic market, which had up to that point seen a very large influx of cash and investors in a globally buoyant environment.

The market is divided between Large Cap transactions (> €300 million) and Small & Mid Cap deals. Large Cap financing has become more complex, with fewer new deals concluded in 2023. Most transactions are carried out with debt funds. Since end-2023, however, banks have again been able to syndicate their loans as market liquidity has improved.

Meanwhile, the Small & Mid Cap market is still active, but lenders have proved highly selective over the last two years. With cost of debt growing excessive, combined with considerable macroeconomic contingencies, leverage has undergone a structural decline; and with often-sensitive margins on the rise, we are seeing a favourable adjustment in risk/return for lenders, including debt funds. At the same time, subordinated/junior debt (PIK[2], Mezzanine) have made a comeback after virtually vanishing, helping offset this reduced leverage.

The macroeconomic environment, significantly less favourable than just 2 years ago for borrowers, has sparked slightly higher default rates and more frequent cases of restructuring and distressed[3] debt.

Conversely, investors receive attractive returns. Currently, single-tranche debt serving to finance a high-quality company generates a gross annual return of 11-12%[4].

Selectiveness: a critical component

Over the last fifteen years, borrowers may have enjoyed record low-cost financing conditions thanks to super-low, if not negative, interest rates, but today they are facing a new, much less favourable reality.

Against this backdrop, some companies are finding it difficult to obtain financing. This is especially true for cyclical firms (retailers, certain industries, etc.), turning little to no profit, subject to management changes, hurt by inflation (raw materials, wages) or predominantly dependent on a single client.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, certain non-cyclical sectors such as health care offer recurring revenues, high margins, low CAPEX, high barriers to entry and leading or co-leading positions on their market, proving highly attractive to lenders.

For Private Debt funds, selectiveness and risk identification are decisive factors for lenders. Enhanced due diligence, close relations and ongoing communication are also critical.

Incorporation of ESG criteria is gaining momentum

Over the last several years, incorporation of ESG criteria in private debt instruments has become a top priority in a bid to meet strong demand from investors and companies alike, aiming to prove that they can obtain green financing.

Certain innovative types of loans place a premium on ESG. One example is the ESG Margin Ratchet Loan, which links the interest rate to the achievement of environmental, social or governance objectives such as reducing GHG emissions. The widespread use of these instruments, though sure to become more streamlined, will undoubtedly prove attractive at every level.

1Single-tranche debt is senior debt that is repayable at term.

2 A PIK (Payment in Kind) is a loan where interest payments are not systematically made in cash. Interest can be paid with another debt security, securities issued by the borrowing company or by issuing stock options.

3 Credit in difficulty

4 In H2 2023: 3% arrangement fee + 3.9% 3-month Euribor + cash coupon ranging from 6.25% to 7.25%.