Growth challenges

The idea that the big economies have gone 'ex growth', that we face 'secular stagnation', has been received wisdom for at least a decade now. How worried should we be?

If growth were to stop, it would mean an end to the rising average living standards that have characterised modern life. Economic development, and investing, would become a zero-sum business in which relative living standards and earnings might change, but total output couldn't. The cake would get no bigger: slicing, not baking, would be the name of the economic game.

That needn't be a bad thing: we might be content. And it is intuitive to expect some limit on growth. Diminishing returns and enjoyment might drive marginal gains down towards nothing. Full capacity and satiety surely lie ahead at some stage.

But a bigger cake makes it easier for us to be reconciled to our individual slices: growth is a sort of political lubricant. And each time economists have presumed to identify the limits to growth – starting with Malthus – they have been premature. We suspect this time is no different.

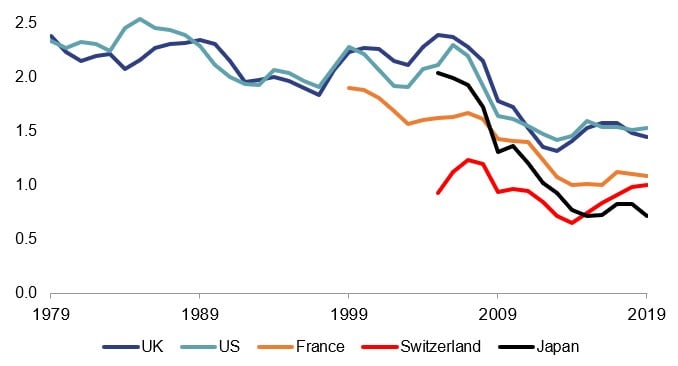

The chart shows trend growth rates in several important developed economies.

Trend growth in GDP per capita for a selection of important developed economies, 1979-2019

25-year compound annual growth (%)

Source: Datastream, Rothschild & Co

'Trends' here are 25-year compound annual growth rates. This is long enough to represent a generation, but it does reduce our sample size (no unified Germany and eurozone, for example). We stop at 2019: COVID-related lockdowns distort even such long-term trends.

We use GDP per capita, not raw GDP. This is most relevant in the wider economic context, and it sidesteps any slowdown which might be attributable simply to there being fewer people available to an economy. To revisit the earlier analogy, it represents the average slice of the cake.

Apart from Switzerland, which has had broadly stable (but already slow) growth for some time, each country has seen a marked slowdown after the 'noughties. Japan's is most pronounced – and even though we're talking about GDP per capita, this might partly reflect Japan's well-known age demographics – but the US, UK and France all saw noticeable (in the chart above) slowdowns.

Slowdowns, but not full stops. Average living standards have not stopped rising. And by 2019 things seemed to be bottoming or even reversing. In the US and UK, the slowings were similar, at around a percentage point per annum. They look significant, but several points need to be kept in mind:

- GDP is hard to measure, and as services and digital output account for more of what we produce, it gets more so. Reviewing UK statistics in 2015, Sir Charles Bean suggested this might account for perhaps half a percentage point of unrecorded growth each year; others have reached a similar conclusion. The slowdowns coincide with much digitisation.

- If we think global growth was flattered by financial excess before the financial crisis of 2008, then it was not sustainable to begin with, and some slowing was inevitable.

- The slowdowns did not stop unemployment rates falling, and labour participation rising. This might mean worsened (measured) productivity trends, but if you grew up in the shadow of higher unemployment it is surely a good thing.

Why are pundits so receptive to the stagnation idea? Several reasons perhaps.

Two high-profile issues, namely debt and demography, are widely misunderstood. As we note here often, neither need pose a significant long-term headwind to the global economy. Received wisdom here is just plain wrong.

More subjectively, we detect a rose-tinted view of the past. We see it, for instance, in much nostalgic writing about the gold standard, which in the end simply didn't work very well. We also see it when economists say there is nothing significant left to invent – even as they worry about finding alternative, non-carbon-based energy sources, or more potable water.

A related reason is the idea that the planet simply cannot afford further economic growth. But if what we consume continues to evolve, and becomes still more intangible, its environmental footprint will be more sustainable. Arguably, the need to mitigate and (especially) adapt to climate change represents one of the more obvious opportunities for long-term growth, not a cap on it.

Ultimately, there are only two key drivers of long-term per capita growth, of higher living standards. These are the learning curve, and innovation. Neither of these has been exhausted.

And a misguided attempt to kick-start an engine which has not stopped could lead to policy mistakes. For example: central bankers' notions of lower 'equilibrium' interest rates; the Truss budget here in the UK; an emphasis on inequality rather than poverty. An overly-pessimistic view of the future may also depress short-term hiring and investing, leading to missed opportunities.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.