Thematic Insights – The Asian Century

Idea in brief: The Asian Century

A demographic titan

With 4.3 billion inhabitants1, EM Asia accounts for 55% of the global population.

Economic prowess

The majority of the world’s most populated cities can be found in the Emerging Asia bloc2. By 2030, the region will be home to more than half of the world’s middle class3. Between 2021 and 2040, Emerging Asia is expected to contribute 55% of the global increase in the consumer middle class population (defined as those with an annual income > USD 5,000)4.

Long-term growth prospects

Within the world’s largest and most dynamic continent, Emerging Asia includes many of the world’s fastest growing and largest economies such as China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam7.

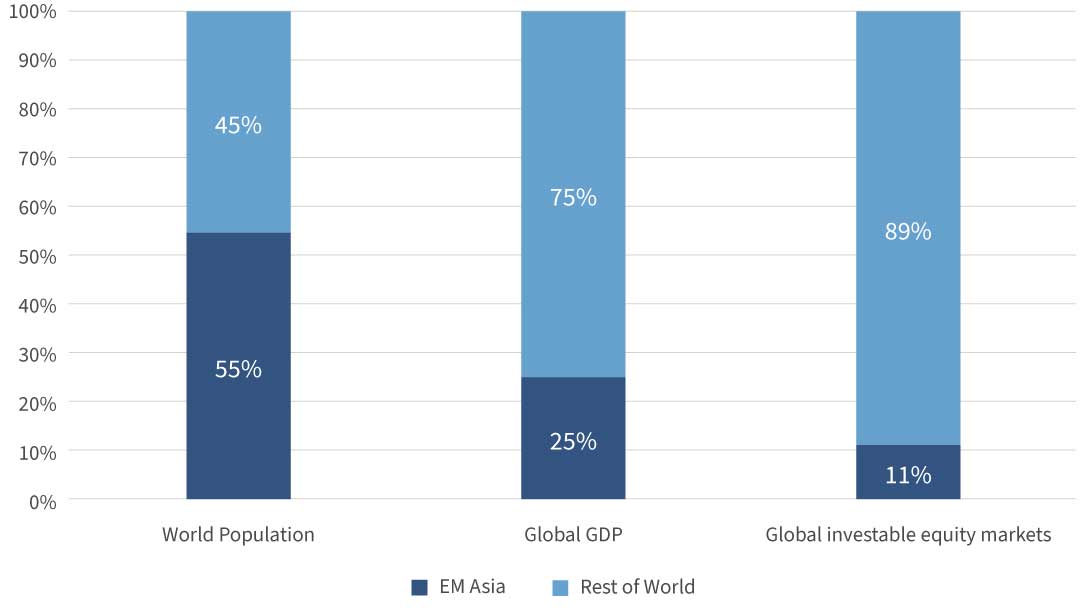

Today this region accounts for a quarter of global GDP, and a far smaller proportion of total investable equity markets (Figure 1). Yet with most of the world’s population living in the region and its economies both diversified and sophisticated, we expect the global economy, and its capital markets, to continue to gravitate towards Asia over this century.

Figure 1: EM Asia today in a global context

The global economy and capital markets will continue to gravitate towards Asia (GDP in USD terms).

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg.

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg.

Diversified economies

Unlike other emerging market blocs, EM Asia has developed diversified economies thanks to a growing consumer sector and strong manufacturing knowledge (and in some cases an absence of major mineral deposits). Those countries are thus less reliant on commodity prices as a source of income in comparison to other developing regions such as Latin America or the Middle East.

Although often seen as an ESG laggard, China is moving forward with decarbonisation and broader environmental goals. Notably, it today produces almost 75% of the world's solar panels, while European, US and Japanese production has almost disappeared.8 The country is also making fast technological gains in green hydrogen technologies, grid transmission, decarbonization of steel and aluminum, and electric vehicles9.

Ongoing reforms have improved efficiency

A number of initiatives have increased transparency, broadened access to Asia’s capital markets and liberalised trade in recent years. For example, in 2020 China signed together with 14 nations (amongst them are Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a trade deal covering roughly 30% of the world’s population and global output, which entered into force in January 202210 (Figure 2).

China, which remains most central to the wider Asian region, has adopted a more nuanced approach to its capital markets. The Stock Connect (2014) and Bond Connect (2017) initiatives introduced a further 1,400 companies to China’s investable universe, removing a number of foreign investor restrictions. This was supplemented by the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone in 2019, doubling the size of its open market. Alongside this – and, in the short-term, less positively for investors – increasing regulatory pressure have emphasized Beijing’s drive towards social objectives, reiterating its vision for ‘state capitalism’.

Since 2005, China and India Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have grown annually by 7.5% and 11.7% respectively.11 The growth in FDI should have an indirect positive impact on the region's corporate governance with public companies more easily punished today for a lack of disclosure or for environment and social malpractice.

Figure 2: The dawn of a new free trading zone

A major step forward for economic integration in the region.

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg.

Tactical headwinds, but structural strength?

Investors in China have faced a more difficult mix of economic and geopolitical risks of late: covid lockdowns, the regulatory tightening noted above, a distressed property sector, and escalating tensions in the Taiwan Strait. Chinese stocks have inevitably come under some pressure. But while the hit from the virus and from further regulatory intervention pose a threat to growth and investment, their impact may be muted by a supportive policy response – China’s low inflation and strong government balance sheets mean that policymakers have plenty of room for manoeuvre.

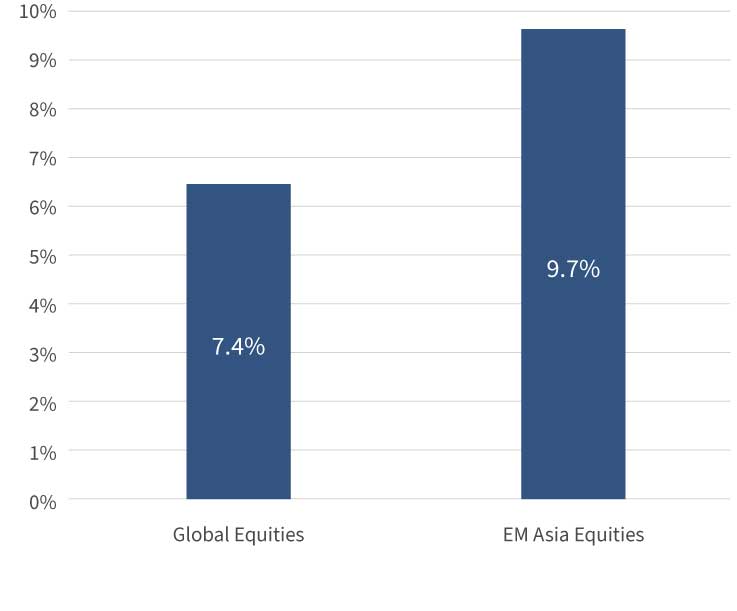

Figure 3: EM Asia's potential equity returns

Reasonable 10-year expectations of nominal, annualised returns (USD).

Source: MSCI, Bloomberg.

Note: Expected return = current yield + growth dividends + change in valuation

Economic Outlook

We currently hold a single overweight in the region. China’s cyclical outlook has improved with the abandonment of its zero-covid stance, and the government is also signalling greater tolerance towards previously penalised sectors.

How to invest in Emerging Asia

There are a number of ways to invest in Emerging Asia to participate in the region’s ongoing performance and long-term potential. Valuations of investments in local businesses are often lower than those in Western companies, but the breadth, complexity and depth of local markets call for expert advice when investing. With our Investment & Portfolio Advisory team at Rothschild & Co Wealth Management, we can advise on the most appropriate ways of gaining exposure to Emerging Asia. We look forward to hearing from you.

1 Based on World Bank estimates, 2021

2 World Population Review, 2022

3 World Economic Forum, 2020

4 Euromonitor, 21/12/2021

5 Based on World Bank estimates, 2021

6 Market Cap, MSCI, Bloomberg

7 Emerging Asia IMF definition

8 APA, China’s Contribution to Low-Carbon Technology Innovation, Sep 2021

9 Climate and Capital Media, April 2022

10 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, December 2021

11 OECD, 2021