Wealth Management: Market Perspective – Keeping at it | Life after debt

Keeping at it

Stable prices, sound money, good government.

Keeping at it is the recent memoir from Paul Volcker, the pre-eminent central banker of modern times. As Fed chairman from August 1979 to July 1987, he rebuilt US monetary credibility after the inflationary excesses of the 1970s.

Early in his tenure, Volcker engineered a tightening of monetary conditions that raised real policy rates from -1% to 9% in less than two years. It was painful, but the Fed did indeed 'keep at it'.

Acutely aware of the importance of the Fed's independence, he 'kept at it' when in 1984 Ronald Reagan's chief of staff, Jim Baker, said - in Reagan's presence - “The president is ordering you not to raise interest rates before the election.” In Volcker's words: “What to say? What to do? I walked out without saying a word.”

Volcker's reputation has climbed even higher in his retirement. He has chaired several important international and domestic committees. The Volcker Rule is part of the Dodd-Frank banking reforms. He talks of sharing his father's belief in the 'three verities' of stable prices, sound finance, and good government.

My favourite quote, with Volcker referring to the current cycle, is “concerns are being voiced that consumer prices are growing too slowly - just because they're a quarter percent or so below the 2 percent target! Could that be a signal to 'ease' monetary policy, or at least to delay restraint, even with the economy at full employment? Certainly, that would be nonsense. How did central bankers fall into the trap of assigning such weight to tiny changes in a single statistic, with all of its inherent weakness?”

The book is a bit nostalgic. Were public ethics so much better in the past - or just less open to scrutiny? As he notes, Mr Trump is not the first president to try to browbeat the Fed. But for me, Volcker is on the side of the angels. Let's hope the current Fed chair turns out half as well.

There are some similarities between Jerome Powell's tenure and Volcker's - and not just the White House tanks on the lawn. Real interest rates have recently been at historically low levels, just as when Volcker took office - for different reasons, admittedly - and now, as then, the credibility of monetary policy is being questioned.

In this context, January's FOMC stance is a little unsettling. In December, we'd said “Bravo Mr Chairman” as Powell resisted presidential and market wishes for lenience. Now, with the economic data not that much softer - as far as we can tell, given the government shutdown, trade-related inventories and contagious market sentiment - the Fed is neutral on rates, and talking of stopping its balance sheet reduction. Keeping at it? Not exactly.

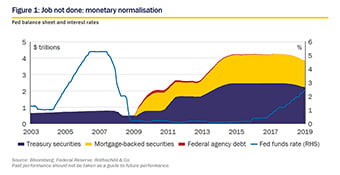

We're particularly surprised at the balance sheet rethink. The argument is that banks these days need permanently higher reserves at the Fed, and that reduced liquidity was damaging the mortgage-backed securities markets, where it coincided with unusually low prepayments and added disproportionately to housing costs. But if the US economy cannot cope with a monthly withdrawal of (up to) $50 billion of liquidity - a shrinkage in the Fed's $4.5 trillion balance sheet since mid-2017 of roughly 10% - then we've misread the bigger picture.

We can't believe the Fed is bending to the political pressure. Instead, it may have been too quick to translate softer data (and that balance sheet reduction) into a bigger recession risk than we can yet see - and/or it is giving too much weight to the forecasting ability (in late 2018) of financial markets.

The Fed has pacified noisy markets. But short-term peace may be deceptive. Long-term investments are best made with a realistic discount rate in mind - and a real Fed Funds rate of around 0.5% is hardly there yet.

This is not 1979. Inflation risk is much smaller than in Volcker's day. But the threat to employment may also be small. As investors, we feel like the guilty parent who gives their crying child a sweet - we like the quiet, but we're not doing their long-term health any favours.

Life after debt

Debt. Small word, big worry.

Debt is certainly transformative: it turns sophisticated economists into superstitious bean counters. The good news is that reality is more nuanced than the popular narrative.

Debt's scariness comes from its fixed element. If circumstances change, the shortfall between that obligation and borrowers' dwindling incomes can widen alarmingly. Such leverage can be vicious. And with more than 7 billion people on the planet, countless businesses and many governments, it can add up to a very big number.

Some perspective

Debt can be a life-changing burden for families, businesses and small countries. But just adding it all up - as some very smart people do - is not particularly useful.

For every borrower there is a lender. As the group we're analysing gets bigger, they start to cancel each other out. The world cannot be a net borrower: we cannot borrow from Mars. If the average person has borrowed $X (opinions vary on what X is - see below), they must have lent as much.

Similarly, it may not be useful to add business, governments and bank debt to individual debt. Collectively, we own businesses and the banks from which we borrow. Our governments borrow from us. Consolidation is needed.

Nor does it make much sense to talk emotively of borrowing from the future. Government bonds can survive us, but will be owned by the same generations that will pay taxes. We can certainly do lasting damage to the economy - if, say, we pollute, or use up scarce resources. But that is a different issue.

Debt and money are often related

Borrowers tend to spend, and rapid borrowing is often associated with faster economic growth. But debt is not a 'factor of production' - an essential input - in the way that real things like labour, capital, commodities and technology are. Debt does not boost total spending power, but redistributes it: lenders have less to spend.

The exception is when the lender is a central bank, or the banking system in aggregate, and able literally to print money. Money is a debt of the banking system - your cash makes you a bank creditor. This complicates things. Printing money can indeed add to total spending power for a while - at least until people realise nothing real has altered, and that money itself must be worth less. (There is a huge literature linking money and inflation.)

Growth in credit is not always associated with new money, and money can grow for reasons other than loan demand. Quantitative easing did not deliver a more dramatic surge in spending because the liquidity created by the central banks did not inspire more consumer borrowing.

… and liquidity can matter a lot

Debt stays put, but money circulates. If the money in use is generated by lending, interrupting that process can squeeze liquidity (and/or push up interest rates).

So when 'the music stopped' in 2007, and some big US institutions were revealed as insolvent, money stopped circulating. The system froze, in a so-called Minsky moment (after an economist who drew attention to such risks).

The system as a whole was not insolvent. The GFC, like most, was a crisis of aggregate liquidity, not solvency. To tackle it, new money was created - not by private loan demand, but by the authorities - and liquidity returned.

Apart from the most reckless loans - write-downs approached $2 trillion - the debt didn't go away. Talk of imminent deleveraging was mistaken: the system needed to be reliquified, not delevered. Hence the global economy could get back to business - it is two-fifths bigger than before the crisis - even as debt grew further. Some of the emergency liquidity created was associated with new debt, which seemed crazy to some - but it was really a liquidity crisis.

Prosperity means big balance sheets

Growing wealth means bigger balance sheets relative to incomes. Sometimes that expansion may be 'irrationally exuberant', to borrow a phrase, but the underlying position need not be precarious. As more of the emerging world's population open bank accounts and borrow, we should be happy for them, not critical.

Some pundits pine for the days when money was linked directly to gold, and banks loaned less. But the golden epoch was illusory: there were crises before 1971, and we were poorer. Cutting the gold link did not lead to a surge in debt-fuelled growth - rather, global growth led to the end of the gold standard. It was too rigid to cope.

Credit watch: it all depends

There is no right level of debt. It is unclear even what the actual level of debt is (see quotations below). Identifying all IOUs is not easy.

Users often play fast and loose with the data. That double-counting is ignored. The amount of corporate debt depends on who's doing the counting - credit analysts only look at indebted companies. In 2010, two Harvard professors overstated Ireland's meaningful international debt by a factor of 10.

If borrow surges recklessly - without collateral or earnings prospects - then cyclical indigestion, and another Minsky moment, can always follow again. Many see China as a current risk. However, its government controls much of the economy, and has plenty of monetary and fiscal room for manoeuvre. China's balance sheet is not tangled up with the rest of the world's in the way that the US balance sheet was in 2007.

Click the image to enlarge

As the IMF notes here - undermining its alarmism - wealthier countries borrow most. Japan's huge government debt, for example, is happily held at negligible yields by prosperous Japanese savers, and has little to do with its economic stagnation.

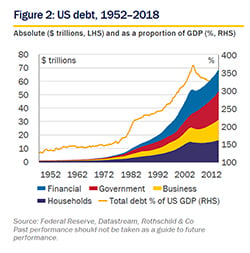

US consumers - the most important customer of Global Inc, and the ultimate US 'bottom line' - have $16 trillion of debt, $2 trillion more than in mid 2007. Relative to GDP it has fallen a bit, but remains high historically. However, consumers have $125 trillion in assets: their net worth is equivalent to more than five times US GDP. It makes US international debt - equivalent to roughly half US GDP - look small.

That wealth is not equally distributed. But debt-obsessed pundits are not primarily concerned with its distribution, but with the headline-catching gross amounts.

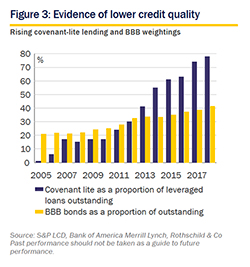

Again, rapid borrowing, especially if associated with new instruments and market segments, can reflect overconfidence, and lead to reversals and routs, if not Minsky moments. It is not good to see lending standards relaxed, and average ratings fall, as in the corporate credit markets of late (figure 3). A tail of highly borrowed companies may yet do some wider damage, and private equity leverage has reached levels that even market participants regard as elevated.

Complexity in finance is rarely good news either. Specially packaged, tiered and collateralised loan securities are again popular, but make it hard for lenders to understand the risk they're taking, and to sell it on. Credit insurance remains unconvincing.

In Europe, bad loans from the last cycle are still posing existential threats to some banks. Some emerging economy dollar borrowers - not China, but other, less diversified countries - look vulnerable again to a rebound in the dollar and US interest rates.

But bank loans have been growing only slowly in this cycle, and low interest rates further mute the risks. And as noted, the structural situation is not as fragile as feared. There is indeed life after debt.

Some of the things they say about debt:

“Total global debt rose… to the second quarter of 2014, reaching $199 trillion, or 286 percent of global GDP.” McKinsey, Debt and (not Much) Deleveraging, February 2015

“Global debt has reached an all-time high of $184 trillion in nominal terms, the equivalent of 225 percent of GDP in 2017. On average, the world's debt now exceeds $86,000 in per capita terms, which is more than two and a half times the average income per-capita… The most indebted economies in the world are also the richer ones…” IMF blog, New Data on Global Debt, January 2019

“…public debt allows the current generation… to live at the expense of those as yet too young to vote or as yet unborn…” Niall Ferguson, 2012

“The pattern of borrowing, spending more than you make, and then having to spend less than you make very quickly resembles a cycle. This is as true for a national economy as it is for an individual.” Ray Dalio, 2018

Investment conclusions

We saw late 2018's volatility as overblown, but stock markets have now rebounded materially. The cycle is more mature, and there is less room for profits to grow after last year's tax-flattered surge. Corporate creditworthiness also seems more likely to fade. We still see stocks as capable of delivering long-term inflation-beating returns - in marked contrast to most bonds - but cyclical conviction must be lower now than it has been for most of the last 10 years (since the GFC) or so.

We still see most bonds and cash as portfolio insurance, not as likely sources of real investment return.

Most government bond markets look expensive, especially as US yields have fallen back, and offer little compensation for inflation and duration risk. Few high-quality yields exceed current inflation rates.

After their rally, we no longer favour high-quality corporate bonds to government bonds in the US. In Europe, where the ECB has now stopped buying, spreads are less tight (over much lower government yields).

We favour relatively low-duration bonds in the eurozone and UK, and now in the US too, though we do still see some attraction in inflation-indexed bonds there. Speculative grade credit did not reach sufficiently attractive levels in the sell-off, and the markets have now rallied - and supply has returned. We still see little appeal in local currency emerging market bonds for multi-asset portfolios.

We still prefer stocks to bonds in most places, even the UK (where the big indices are really global in nature), but after their rebound, we see tactical risk from the ongoing earnings slowdown and/or a rebound in expected US interest rates. We have few regional convictions, but still believe emerging Asia's structural appeal remains intact, trade tensions notwithstanding, and US profitability seems set to stay high. We still mostly favour a mix of cyclical and secular growth, but the balance has tilted more towards the latter.

Trading currencies does not systematically add value, and there are currently few big misalignments among the majors. The Fed's further softening of tone has hurt the dollar, but we expect economic growth and higher initial carry to boost it. In contrast, the euro faces both sluggish growth and an even more doveish central bank. The pound is hostage to Brexit tensions in the short term, but is competitive, and on a long-term view is capable of rallying (eventually) even after a no-deal exit.

In this Market Perspective:

-

Foreword

-

Keeping at it | Life after debt (current page)

-

Economy and markets: background

-

Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (PDF 1 MB)