Wealth Management: Strategy blog – Location, Location, Location

Strategy team - Kevin Gardiner and Victor Balfour (Wealth Management)

Globally, there is roughly $160tn of private residential property, compared with $100tn of debt securities, $80tn of listed equities and $30tn of commercial property. Given the links between housing market finance and banking systems, property booms and busts are unsurprisingly often linked with economic volatility.

Is the stage set for the next episode? The UK, Hong Kong, Australia and Canada for example have shown signs of overheating in this cycle. Prices in some big cities are now retreating. Overall, however, we think the picture is a more nuanced one.

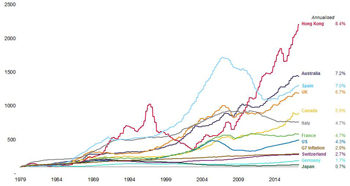

Residential property indices Dec '79 to Mar '18

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bank of International Settlements (BIS)

(Click the image to enlarge)

Performances can diverge markedly, even over the longer term. Since 1979, Hong Kong's residential property prices have grown by more than 8% annualised, or 22x, according to BIS estimates. At the other end of the spectrum, Japan's prices have grown by less than 1% per annum, and are down two-fifths from an early '90's peak.

Italy, the UK and Australia were some of the best performing housing markets up until 2008. The latter continued its upward trend barely affected by the crisis - alongside the Australian economy's 27 years of uninterrupted growth. Conversely, UK prices took over six years to recover from the GFC slump before resuming a pre-crisis pace of growth. Italy's property market has taken an entirely different trajectory, down 25% from its 2008 peak- which helps explain the bad loans at Italian banks.

The US property market is fragmented, but nonetheless slumped between 2007 and 2011. A quarter of American homeowners were in negative equity at one stage - versus 5% currently. The US real estate market only recently reclaimed its pre-crisis peak (it is now 3% higher).

German home ownership is low relative to the UK or US, and the property market doesn't exhibit the same 'boom and bust' cycle of other property markets.

Since 2009, property prices in some markets have outstripped wages significantly. Household debt (mortgage debt is usually the lion's share) has continued to increase as a proportion of GDP in Australia, Canada and HK. Many household debt service ratios (interest payments and scheduled principal repayments divided by income) have however remained flat or fallen. Household debt has declined relative to GDP in both the US and UK since 2010 - reflecting restrained new borrowing and growing GDP.

Home-ownership can change. In the UK, declining affordability has cut it to its lowest level since the mid-80s, and the number of renters has doubled in the past 15 years. In the US too, there are signs that the severe downturn in 2008/09 has reduced appetite for ownership.

The sheer size of global residential property (1.5x GDP) and its financing make property cycles a concern. Outright 'bubbles' are rare however (1980s Japan being a notable example) and many alleged property-induced recessions were likely also driven by other factors, including policy mistakes.

US housing excesses, particularly in the sub-prime segment, fostered the GFC of course. Risks were obfuscated, and rising defaults led to a global liquidity crunch. But prices across US major urban areas are at new highs. Were they so unsustainable after all?

The cooling of overheated markets now need not portend another crisis. Idiosyncratic issues may be playing a part. Much slower growth in bank lending in the US and UK in particular in this cycle suggests systemic risks are smaller.

Investment conclusion?

Real estate may not pose an imminent threat to the wider economy. What about its attraction as an investment?

It offers a genuinely different, and often uncorrelated, third source of investment returns to go with interest income and company profits. And as noted, while some markets have overheated, a widespread slump currently seems unlikely.

But residential real estate is not always as 'investible' as it sounds. Choosing a home is one thing, but scaling up multiple properties into bigger investments can be more difficult. Taxes and management fees can be significant. 'Open ended' funds can leave investors sidelined in cash, or forced into distress sales. REITs behave more like stocks than property. Direct investment is by definition illiquid.

As a result, the two conventional sources of investment returns are easiest to build into most portfolios. And lower-cost equities have historically done better than most residential property indices.

Disclaimer

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.