US dollar momentum

The greenback has remained strong this year.

The DXY index, a gauge of US dollar strength vis-à-vis a basket of six major currencies, has risen by 4% in 2024. The euro has by far the largest weighting within the cohort, at close to 60% of the total. But the US dollar has still appreciated against the remaining currencies on a bilateral basis, including the pound (+2%), Canadian dollar (+4%), Swiss franc (+8%), Swedish krona (+8%), and most strikingly, the Japanese yen (+10%). Moreover, most emerging market currencies have also weakened against the dollar this year.

The return of the dollar smile?

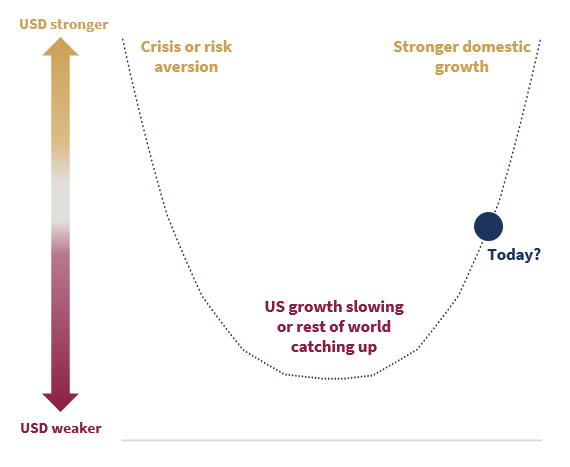

There are a lot of moving parts behind fluctuations in exchange rates, including economic variables such as inflation, interest rates and balance of payments, and wider developments in fiscal policy and politics more generally. However, the US currency often seems to perform well under a wide range of circumstances, leading to the notion of 'the dollar smile', popularised by economist Stephen Jen a couple of decades ago.

The idea captures the tendency of the dollar to do well when the US economy seems to be doing particularly well, but also when it is doing particularly badly – that is, it often seems to be only when the US economy is in the mediocre middle ground that the dollar struggles (figure 1). The idea is more intuitive than it sounds initially: at times of US economic exceptionalism, investors flood in to take advantage of US assets and interest rates; at the other end of the scale, when the US is doing really badly, we are likely facing some sort of global crisis, and the dollar appeals then for its ‘safe haven’, reserve asset status.

Figure 1: The ‘dollar smile’

Source: Rothschild & Co

Source: Rothschild & Co

Currently, the dollar’s upward momentum may be underpinned by better relative US growth. Recent GDP outturns have been stronger than in the other advanced economies. US growth estimates for this year have been revised significantly higher, while Europe’s, for example, have been broadly unchanged. The relative ‘carry’ story is related to this: partly because of this growth, US interest rates are higher than elsewhere, and the gap seems if anything likely to widen – though only modestly – as the Fed drags its heels over rates cuts.

There are of course exceptions to this theory, usually when the US itself is the focus of perceived risk. For example, during the short-lived US regional banking crisis in March last year, the DXY index briefly weakened by nearly 5% in the space of a month.

This is not the 1980s…

As the 'smile' idea suggests, US dollar strength is not ‘new’ news. The US dollar has appreciated notably over time according to broader trade-weighted indices, and persistently so against the major ones in the last decade (the Swiss franc being the exception). However, there is no obvious ‘line in the sand’ beyond which the dollar becomes wildly expensive, or widespread, coordinated currency interventions begin as policymakers try to arrest its rise.

Despite the adoption of flexible (and eventually ‘fully floating’) exchange rates – after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early '70s – central banks have often intervened in currency markets. Most recently, the Bank of Japan reportedly propped up the yen after it had declined to its weakest level in more than thirty years against the dollar (to be fair, this was not just a ‘strong dollar’ story, as the yen has weakened against most major currencies in recent years alongside Japan’s extremely lenient monetary policy, which persisted even as the other major central banks were raising rates from 2021-22).

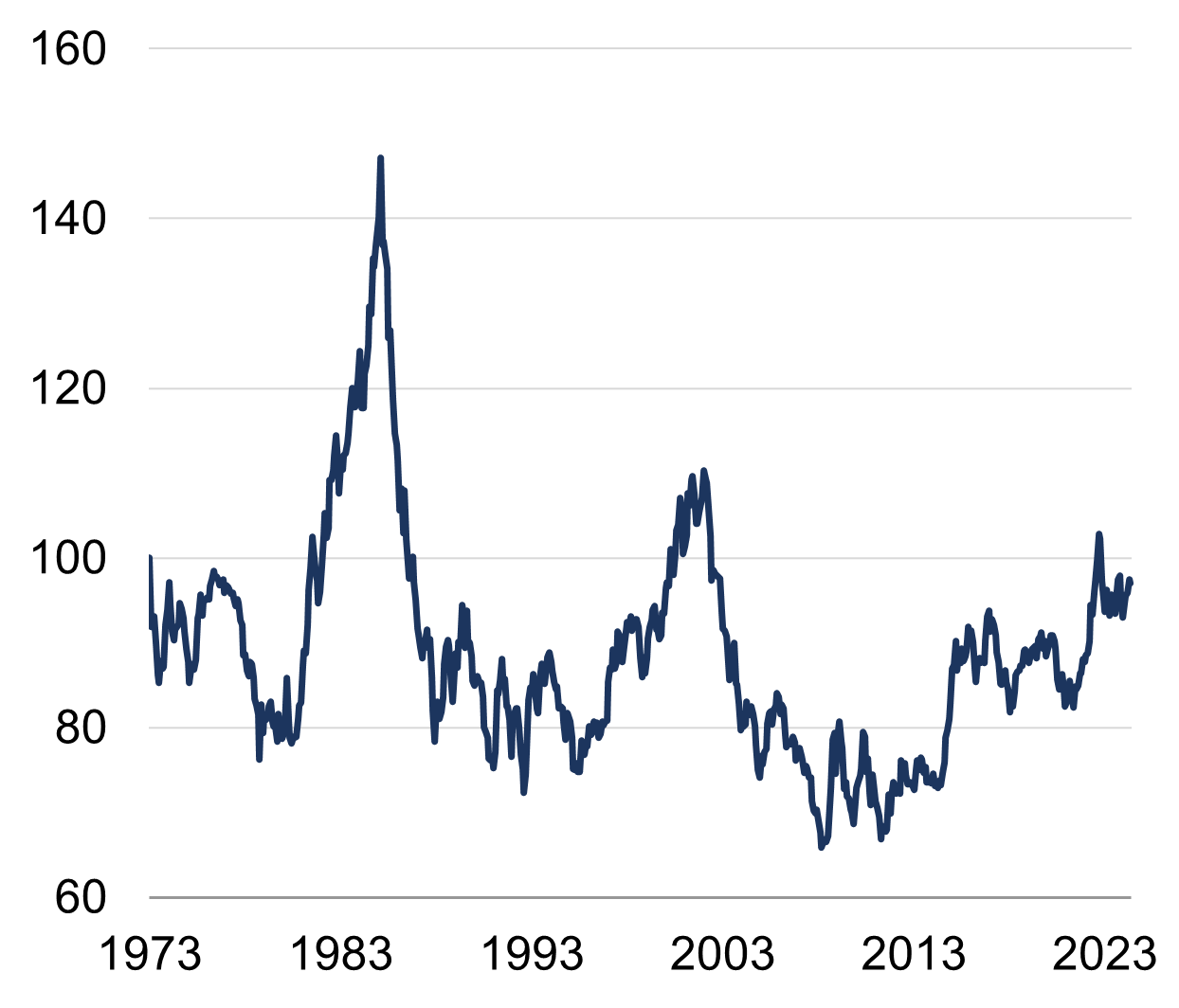

The most famous example was perhaps the Plaza Accord in September 1985. Over the first half of the 1980s, the US dollar experienced a sharp appreciation – the DXY index almost doubled – partly due to a mix of tight monetary policy and fiscally-led loose growth in the US. Concerned by the US trade imbalances and the ‘exporting of US inflation’ that might result from a stronger dollar, the G5 cohort coordinated a joint effort to bring down the value of the greenback (the Louvre Accord followed in 1987, to halt its subsequent sharp decline).

Meanwhile, today’s backdrop is somewhat different. The DXY index has been trading in a relatively tight range for more than a year. It is roughly a third below its all-time high from 1985, and it is even 7% below its more recent 2022 high (figure 2).

|

Figure 2: DXY index over the long run Rebased indices (January 1973 = 100)

|

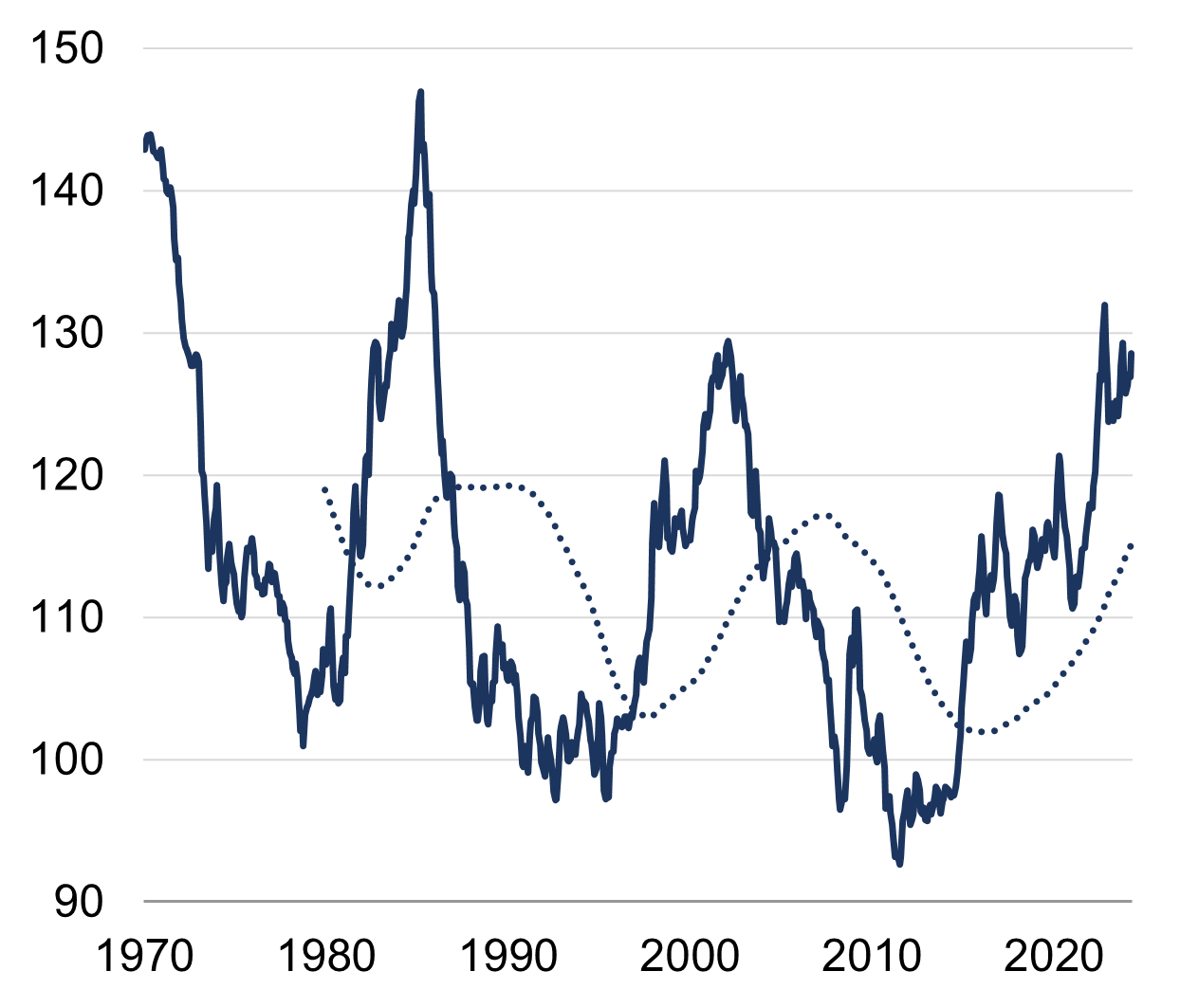

Figure 3: US real broad trade-weighted exchange rate Relative to 10-year trend

|

Admittedly, broader trade-weighted indices suggest that the US dollar is much closer to its all-time high (as noted above), having reached that threshold in 2022. Yet, the broader exchange rate does not appear egregiously expensive. Real – or inflation-adjusted – currency indices can be used to gauge how expensive the US dollar is, and the JP Morgan index shows that it has been at these levels before and is well below its 1985 peak (figure 3). While it remains above its perceived ‘fair value’ – its ten-year rolling trend – it’s worth noting that currencies can deviate from their real trends for long periods of time (in other words, they are not a short-term timing tool).

Conclusion: no strong directional view

Currencies are the most transparent and efficient dimension of global capital markets, and we need to have high conviction to make a strong directional call. Such conviction remains in scarce supply, and as noted, the major cross rates have not been especially volatile in the last year or two (rather the opposite).

Fluctuations in the dollar can impact portfolio returns, and an unhedged dollar-based global investor has slightly lower returns this year compared to a sterling or euro-based investor – but stock market volatility is usually the main driver of returns, not exchange rates. This could change of course.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, JP Morgan

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, JP Morgan