The defence debate

‘Are we to become so entangled in European high-pressure politics that the main issue at our elections will be whether or not to allow political changes abroad?’

General Smedley Butler’s ‘War is a Racket’ offered a fiercely cynical, sobering assessment of the economic costs (and benefits) of conflict. In a 1933 speech (later transcribed into a book) he urged the US to pivot towards neutrality and the defence of its own borders, and no longer seek to profit from war.

Nearly a century on, and an increasingly inwardly looking Donald Trump seems to share some of these very same sentiments – albeit perhaps without the eloquence.

The events of the last couple of years have dramatically increased the geopolitical temperature – a war of attrition in Ukraine, the re-eruption of conflict in the Middle East and talk of an economic Cold War between the US and China. The rise of the ‘known unknowns’ has shifted the political discourse in favour of security.

The US election campaign is gathering momentum and the fiscal realities of funding a war loom larger. Fiscal fatigue amongst Ukraine’s allies and Europe’s diminished ability to defend its own borders is re-igniting the debate over military spending and NATO commitments. NATO Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg, recently asserted that an ‘alliance of authoritarian powers’ threatens the West.

As ever, there are some big, thorny questions. Does Russia have territorial designs on the Baltic states? Will the US pivot away from NATO? Will the Franco-German axis fill the void? How will already strained budgets accommodate such spending?

US: rhetoric versus reality

The US’s absence from NATO would be felt keenly. The key pillars of deterrence and defence would be deeply weakened.

Trump has been a long-standing critic of NATO – since well before Russia’s attack on Ukraine – citing the US’s disproportionate spending on military. He has a point: last year the US spent 3.5% of GDP or $860bn on defence – close to double what the rest of the Alliance collectively spent. The reality is that many countries are simply unwilling (or unable) to meet the required 2% of GDP. In 2023, only 11 out of 31 member countries met the target, with France and Germany failing to spend the requisite amount. Ukraine’s need is large: the Kiel Institute estimates that it has received $430bn of (mostly military) aid, more than half of which has come from the US.

What Trump says (if he is elected) and what he does may be two quite different things. But this does not seem to be a re-run of the old ‘Guns vs Butter’ debate: Trump is unlikely to prioritise welfare and social programmes over defence spending, for example. His latest salvo suggests that if European countries ‘play fair’ then inaction – the status quo - remains the most likely way forward.

There is also an important backstop: a chorus of military hawks on Capitol Hill that will continue to drive the US’s engagement with NATO and support Ukraine. The Senate recently passed a $95bn aid bill (yet to be passed in the House, where a group of hardline Republicans continue to withhold support). Arguably the US benefits economically from its informal role as global peacekeeper – for example by securing trade routes and projecting soft power.

Europe to bear arms?

Even with ongoing US support, attitudes in Europe have shifted dramatically. The days of ‘constructive engagement’ with old Cold War opponents may be over and a new militarist movement may be gathering momentum. February 2022 marked a turning point, ‘Zeitenwende’, in Germany’s political priorities, with Scholz reaffirming its commitment to 2% and beyond. The recently enlarged NATO, bolstered by Finland and Sweden’s accession in 2023 to the alliance, testify to this evolving backdrop.

How Europe addresses the big economic and military obstacles is far from clear. Division, and the absence of a long-term strategic plan, have hindered efforts to date. For example, Macron’s recent assertion that Western troops might be sent to Ukraine was curtly dismissed by his counterpart, Scholz. Until the Franco-German axis is able to formulate a strategy, other countries will be reluctant to follow suit.

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, has recently announced plans for a common EU defence strategy. But whether such plans become reality will depend on fiscal priorities. Most debt burdens are at or above 100% of GDP, and deficits are elevated, there is limited fiscal headroom. The exception is Germany, which remains committed to ‘black zero’ (that is, no borrowing) and remains the most vocal opponent to a common EU budget. However, the EU pandemic recovery fund – the first (major) attempt to mutualise European debt – perhaps offers a credible blueprint for collective borrowing and spending on defence initiatives. And the reality is that another percentage point or even two on top of current projected deficits is hardly a fiscal game-changer.

The implications

The notion that conflict is ‘good’ for economic growth speaks to the callous nature of national accounts. Armaments and a bigger army count towards measured growth, while the loss of life and buildings does not count against it. As we’ve noted before, GDP as a concept has its limitations.

However, while those accounts remain the arbiter of economic debate, more spending – whether funded debt or money printing – will suggest more growth and/or more inflation ahead. To some extent a defence-industrial boom has already been playing out in the US: production of defence equipment rose 12% in 2024, while defence exports and durable goods orders have been surging.

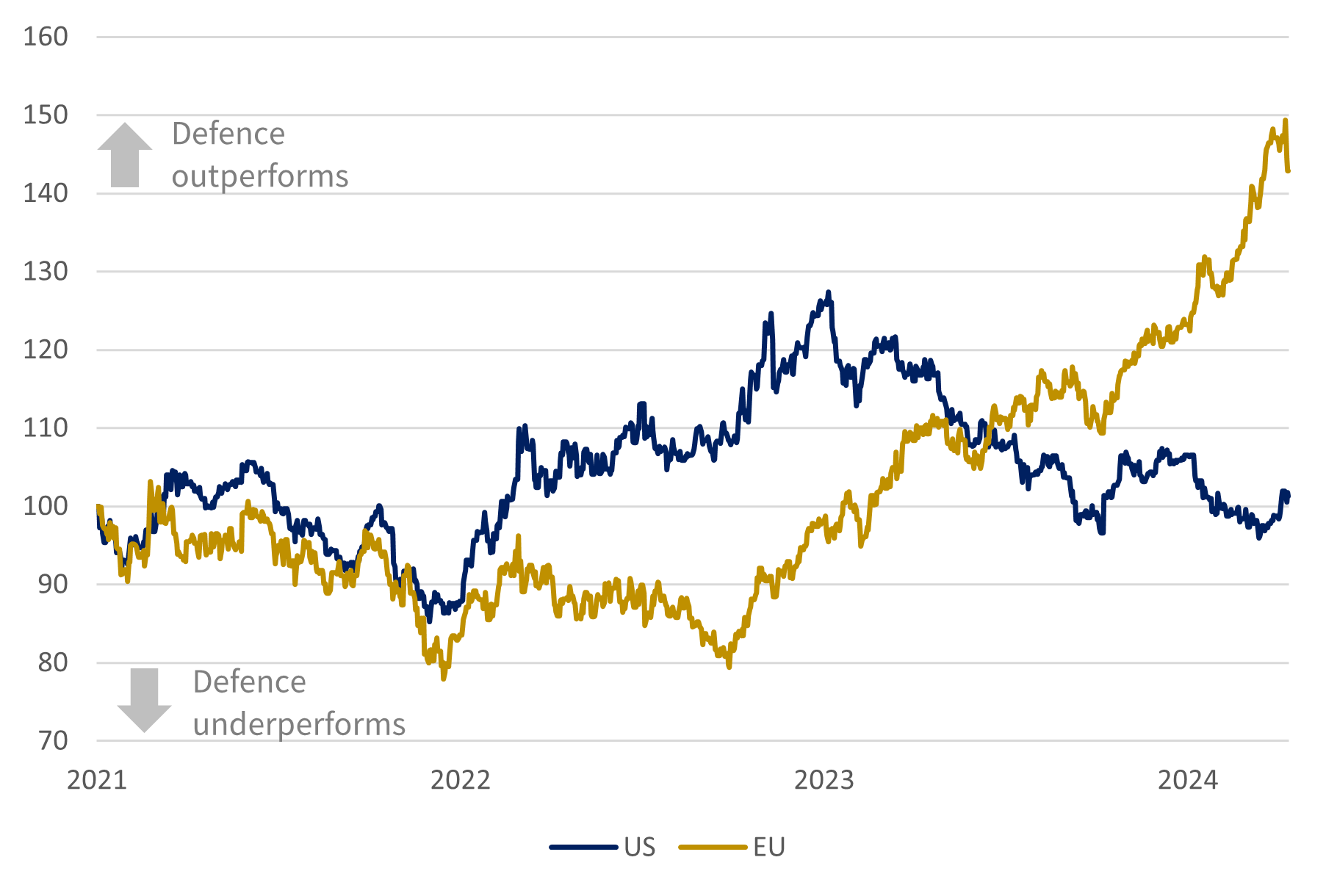

Whether a similar surge now extends to European industry and Europe’s defence companies remains to be seen. The largest such companies are found in the US, and years of underinvestment in manufacturing capacity will not be reversed overnight. But investors may not have been waiting to find out: European defence names have already outperformed in the past couple of years and valuations are no longer cheap. Surprisingly, the US cohort which benefitted in the early stage of the war have since fallen back.

Of course, even if political rhetoric eventually translates into more concrete spending, the evolving nature of defence suggest military equipment producers may not be the only beneficiaries.

Defence stocks relative returns (100 = Jan 2021)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, MSCI, S&P Global

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Correct to 10 April 2024.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.