Tailwinds for the UK consumer?

The recent UK retail sales data hit the headlines – but for the wrong reasons.

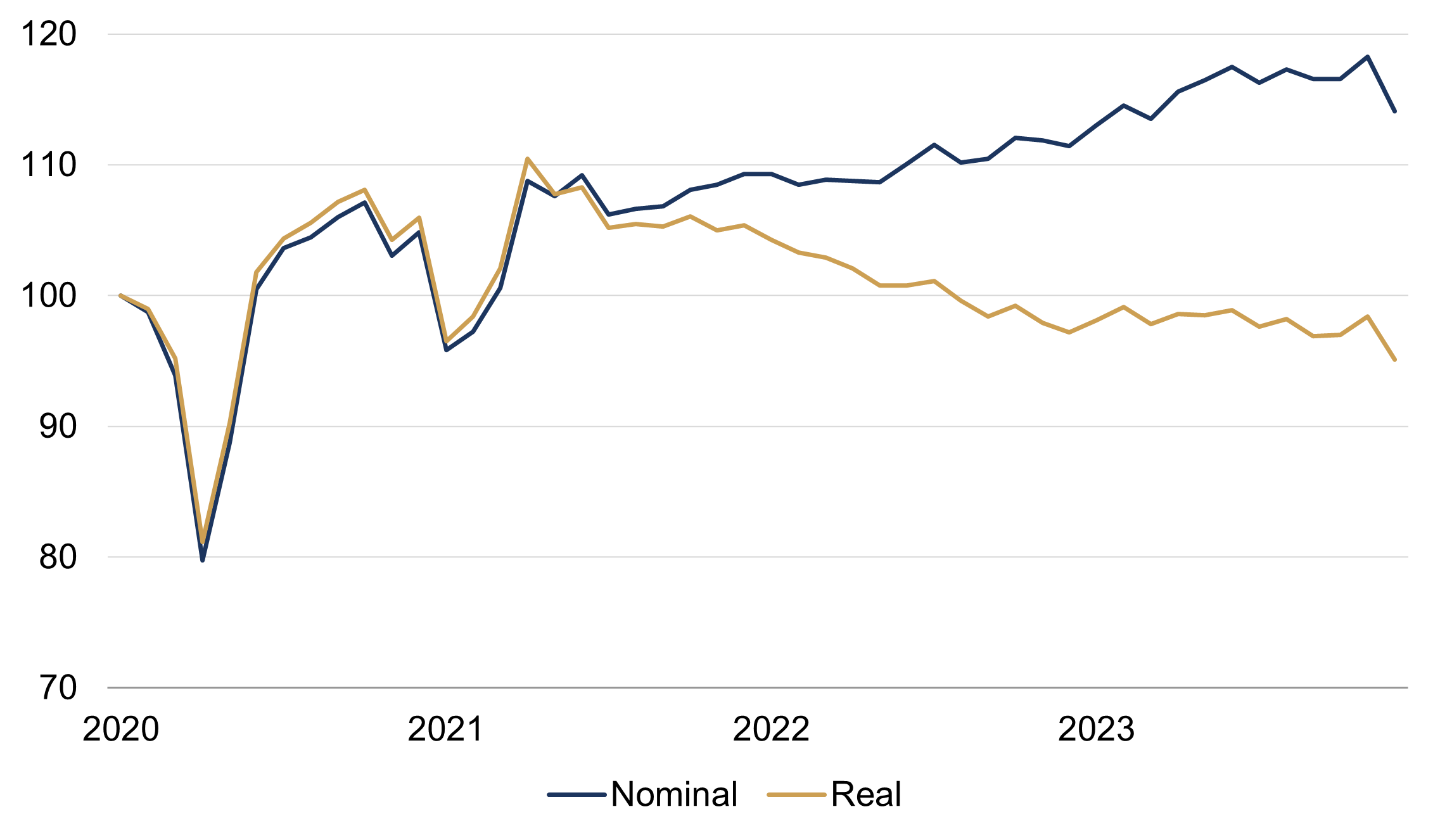

Core retail sales unexpectedly declined by 3.3% in December, the weakest monthly print since January 2021, when there was a pandemic-related national lockdown. Some of the weakness was attributed to unusually wet weather, while other commentators suggested it was partly due to Black Friday sales taking place earlier than usual. Nonetheless, real (inflation-adjusted) retail spending has been trending lower for close to three years and is 5% below its pre-pandemic level (figure 1).

Figure 1: UK retail sales ex automotive fuels

Rebased indices (January 2020 = 100)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Office for National Statistics

However, retail spending only accounts for approximately 30% of total consumer spending. The latter, roughly two-thirds of UK GDP, is actually holding up much better. And there is a good chance it will continue to do so.

Hefty savings ammunition

There are two key variables which influence consumer spending: things which affect disposable – or spendable – income, and changes in the proportion of that income which is spent (or not: in practice, the convention is to talk more about the inverse, the savings rate, which goes up as the proportion of income which is spent falls). These two variables are themselves shaped by other causal factors such as confidence, wealth effects, and so on.

The household savings rate has increased since the middle of 2022 – perhaps not too surprising given rising interest rates and gloomy media headlines – and is now unusually high at 10%, well above its pre-pandemic average. Looking ahead, this means that households have plenty of room to spend if interest rates fall or if they feel more confident. Surveys of confidence have in fact rebounded, and interest rates seem likely to (gradually) fall this year.

Meanwhile, a rebound in real disposable income seems likely as real wages continue to revive…

Energy costs are still falling

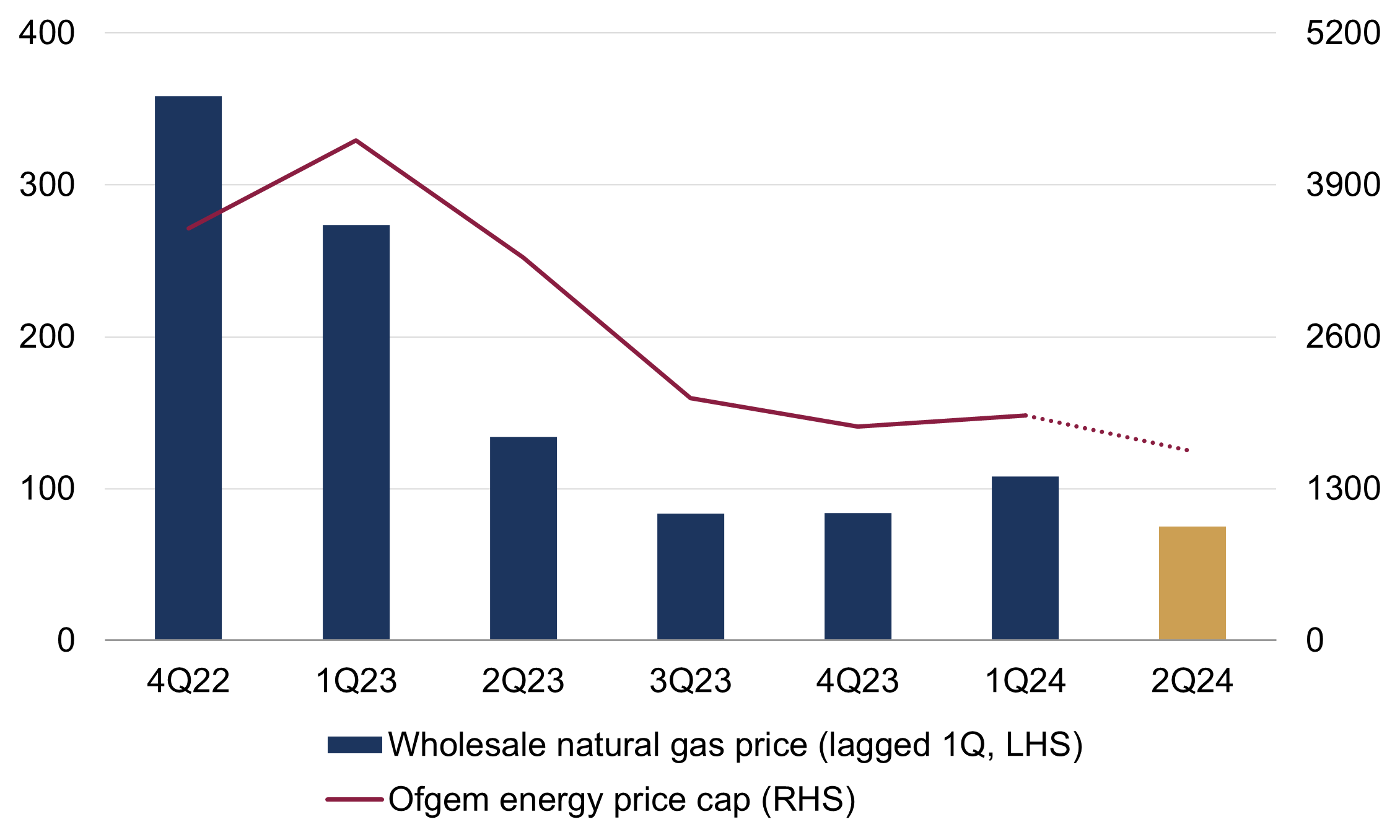

The energy shock is now moving into reverse. Wholesale natural gas prices have been trending lower for a year and a half – albeit in a volatile manner – and, more recently, have nearly halved in the space of three months.

Ofgem's energy price cap has fallen sharply from its highs, and after a brief rebound in December is set to move lower again next quarter, with most estimates suggesting a 15-20% decline (figure 2). Governments in continental Europe have been using analogous schemes, and so consumers there should also experience a similar reduction in their energy bills.

Figure 2: UK natural gas prices and the Ofgem energy price cap

Left axis = average daily price (pence per therm); Right axis (GBP per year)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Ofgem

Note: Wholesale natural gas series has been lagged by one quarter

Of course, a renewed surge in energy prices can't be fully ruled out: critics will argue that Europe has been fortunate to experience a warm winter so far, and escalation in the Middle East may cause oil prices at least to rise again. But Europe overall has adapted to the initial surge: gas storage levels are close to record seasonal highs, despite the curtailment of Russia's pipelines.

Mortgage rates have peaked

Interest rates can impact consumer spending through various channels, but the most direct one is via higher mortgage rates. Total household incomes can actually benefit from higher interest rates, through the sector's large savings balances. In practice, however, households with mortgages cut back by much more than households with savings splash out, and so the net effect of higher rates on spending power is usually negative.

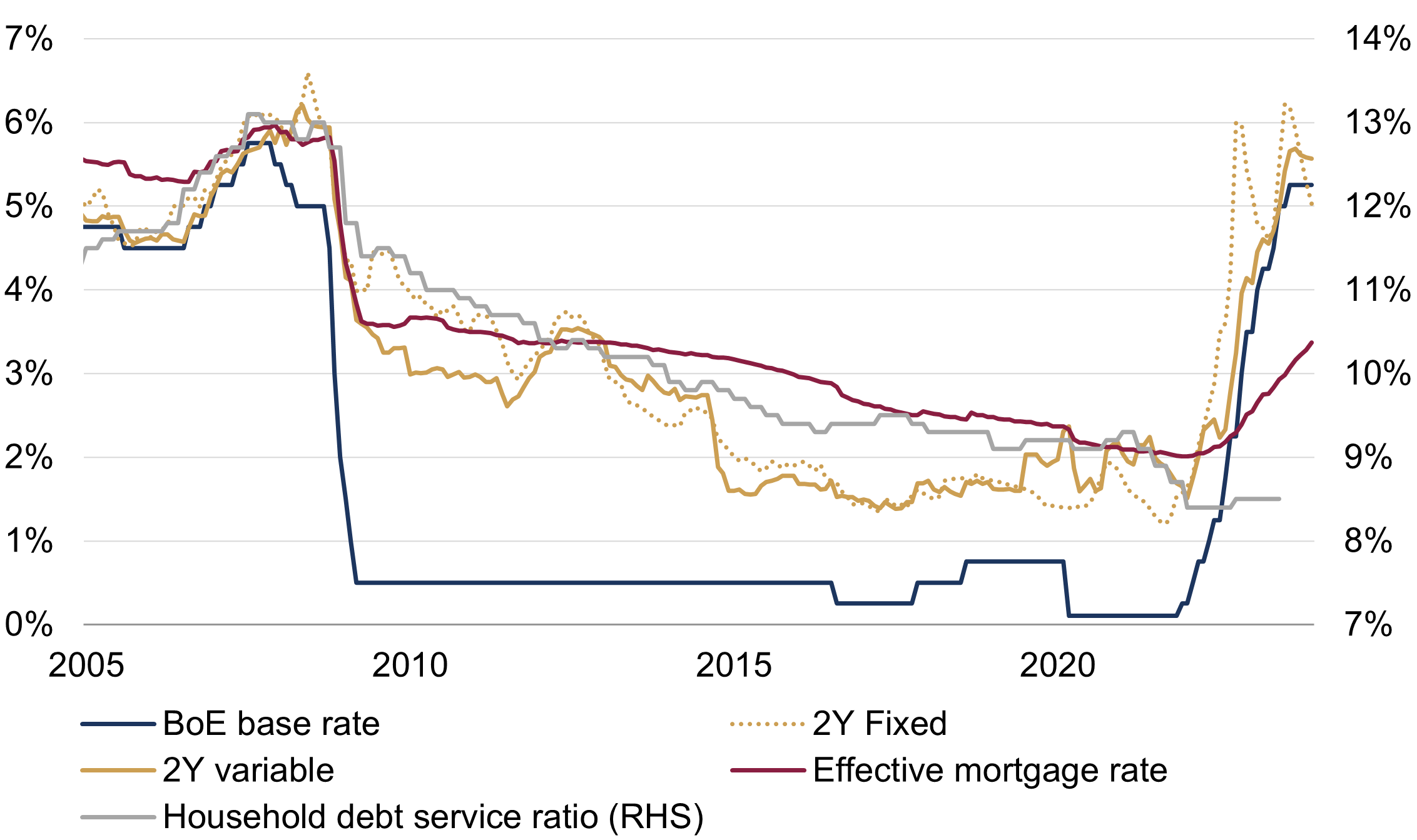

The effective mortgage rate – a gauge of the average interest rate actually paid by homeowners with mortgages – is still almost two percentage points below the Bank of England's base rate. More than half of outstanding mortgages were on a five-year fixed rate during the third quarter of 2022, according to the Office for National Statistics.

The Bank of England will likely start to cut rates this year, and some mortgage rates have already started to decline in anticipation: two-year fixed rates have fallen by more than a percentage point from their peak in July, and even variable (tracker) rates seem to have topped out (figure 3). The effective mortgage rate may rise from here as more people roll off their fixed rates, but a dramatic surge seems unlikely.

Figure 3: UK interest rates

(%)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg, Bank of England, Bank for International Settlements

Note: Two-year fixed and variable rates are based on a 75% loan-to-value ratio. Effective mortgage rate applies to all outstanding mortgages. Household debt service ratio is interest payments relative to income and is only up to the second quarter of 2023.

Most households are in fact shielded from higher mortgage rates nowadays. Only 26% of households in England had an active mortgage in 2021 – down six percentage points from 2012 – while a fifth were privately renting (admittedly, rents from landlords on a flexible rate buy-to-let mortgage will have risen). The proportion which owned their homes outright was 37% in 2021, and the remainder (roughly 20%) were rented from the public or social sector. This also explains why household debt service ratios – interest payments relative to income – were still remarkably low last year (see figure 3, again).

Conclusion

Consumer spending is not as weak as retail sales make it appear, and there may be some growing tailwinds this year. Of course, the domestic UK economy may not matter so much for globally oriented portfolios. But it may yet play a role in the UK election outcome (see here).

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.