'Greedflation'

Are companies partly to blame for the post-pandemic inflation wave?

Most firms have of course raised prices after a variety of supply-side shocks led to higher input prices. But it is suggested that some companies have used this as an opportunity to raise consumer prices by significantly more than the increase in costs. This alleged phenomenon has been termed 'greedflation'. To us as investors, pricing power is a good thing. But to us as consumers, if it reflects price gouging, or monopoly, it is unfair.

It is an understandably emotive idea then, but it is also one which is frustratingly difficult to check. Even in the US, which generally has the most complete macro data, there are few 'input cost' indices available to compare directly with consumer price indices. Producer price indices, for example, have different component weightings to consumer price indices, while the most important input cost – labour cost per unit of output – tends to be published in more aggregate form (and only on a quarterly basis).

Moreover, some products are more volatile than others. When oil prices surge, for instance, it would be surprising if profit margins in the sector generally did not widen. But we often tolerate this as consumers, on the implicit understanding that such movements are likely to be short-lived: we expect the sector to suffer squeezed margins when prices eventually fall back.

We can track profit margins in published corporate accounts – as net income relative to revenue. But net income can be affected by all sorts of things (such as product mix, lumpy fixed costs, scale effects), and it is only a very loose gauge of corporate behaviour.

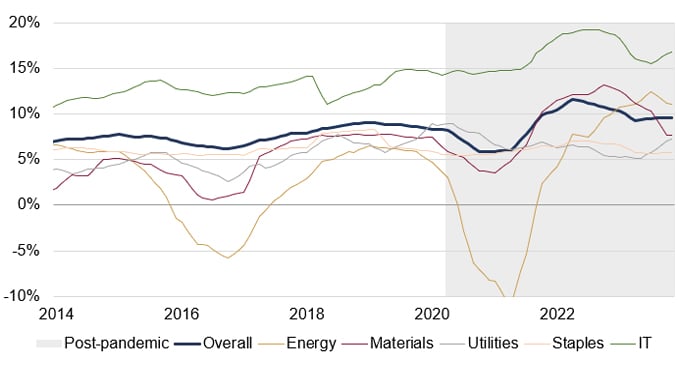

Even so, this data show little sign of 'greedflation': margins for the MSCI World drifted lower in the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, through to May 2023 (Figure 1). Profit margins have crept higher since then and are above pre-pandemic levels, but this is not conclusive: margins were already trending higher on a long-term basis, and until recently were doing so unaccompanied by significant inflation.

Figure 1: MSCI World sector indices (Profit margins, %, three-month moving average)

Source: Rothschild & Co, Bloomberg

At the sector level, Technology profit margins were roughly flat in 2022, as were Consumer Staples (perhaps the most emotive sector, given the claims of food-related 'greedflation' and its potential impact on lower-income households). Utilities have only seen their profit margins increase in the most recent months, despite last year's spike in energy prices (i.e., the cost pass-through to consumers may have been a 'fair' one). The most visible exception is Energy (and Materials to some extent), as profit margins rose considerably in 2022 – but as noted, commodity prices are often volatile, and short-term margin fluctuation may not be that meaningful.

A Bank of England study also reached a similar conclusion (see here). They looked at the ratio of profits (EBIT) relative to value added for all large non-financial listed companies (EBIT + wage and salary costs) in the UK and the euro area. Most sectors had very little change in such profit shares between 2021 and 2022 – apart from the oil, gas and mining sector – as wages, salaries and other input costs rose just as much as profits.

In summary, it is not convincing to blame corporates for the surge in consumer price inflation. This does not mean that all companies have behaved admirably throughout of course – but the average-quoted companies do not seem to have misbehaved egregiously. We continue to see the main drivers of the inflation surge as macro in nature: supply-side constraints and lax demand management.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Speak to a Client Adviser in the UK or Switzerland

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this article constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.