Strategy blog: Inflation - winter is coming?

UK inflation, already at uncomfortable levels, is set to grind higher, peaking at 13% by year-end – according to the Bank of England – followed by only a gradual descent to perhaps 6% by the end of 2023. To date, there has been little to choose between the big western economies in terms of inflation rates, but this may change for a while at least, as US and Euro area inflation seem set to decelerate now.

The pending divergence reflects the persistency of underlying inflation pressures, with core rates in the UK still elevated (and moving higher), alongside the varying impact of energy costs.

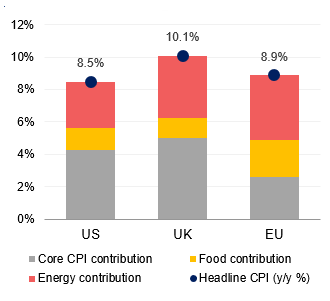

Headline CPI (y/y %) and contribution

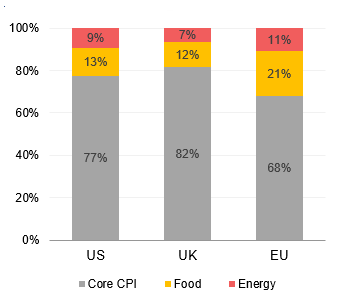

Inflation basket weights

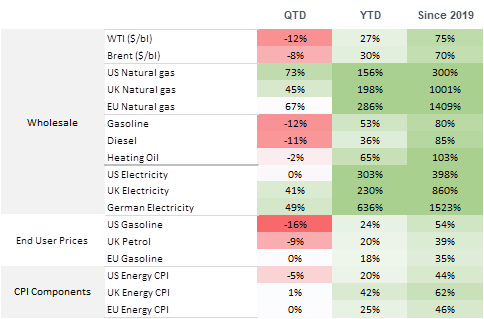

Oil prices are not to blame: these have retreated a quarter from their March high to $95/bl (Brent), as a combination of increased OPEC output has been met by slowing global demand. Even distillate prices – including gasoline and diesel, dogged by refining bottlenecks – have retreated. Instead, it is the cost to households of natural gas - a deeply segmented market to begin with – which will drive headline inflation rates further apart.

UK natural gas futures are up 200% year-to-date, and 11-fold since the end of 2019, whereas European gas futures are up 290% and 15-fold. This is as we’d expect, given Europe’s greater dependence on scarcer Russian gas (and its modest domestic production and limited number of LNG terminals). (Note, by the way, that even the US, which is geographically detached from current disruption and has ample domestic production to satisfy local demand, is not insulated from the global gas squeeze)

Energy prices

Note: Returns are derived from the respective front-month futures contract, apart from ‘Electricity’, which reflects ‘day ahead’ spot prices and gasoline/petrol prices, which are taken from average forecourt pump prices. Data is correct to 19th August 2022 (CPI data correct to 31st July).

To some extent these dramatic wholesale movements are reflected in the contribution that ‘energy’ makes to each of the respective CPI baskets – accounting for half of the headline inflation rate in Europe, but slightly less in the UK, closer to two-fifths. The weight of energy is bigger in the EU CPI.

So why is the UK’s inflation surge bigger, and likely to last longer?

Within the CPI, while the overall weighting for energy is smaller in the UK than in the EU, the natural cost component is much bigger. Gas accounts for nearly 40% of the UK’s primary energy consumption – two thirds more than that of Europe. Not only is gas the primary energy source for household heating (approximately 85% of households) but nearly half of the UK’s electricity is generated through methane-powered plants – double the proportion on the continent (though this varies by country). At the margin, the UK’s growing renewable exposure means that it has less surplus capacity, further exposing UK consumers to more volatile fluctuations in energy prices.

As a result, there has been a more dramatic surge in UK (CPI) energy costs over the past year (+58%) relative to Europe (+38%) – and the administrative context means that there is still much more to come here.

The existence of the UK’s energy price “cap” has delayed the pass-through from wholesale costs. The cap – introduced in 2019 - was designed to prevent ‘retail’ utility companies (not the extractive wholesale producers) from reaping excessive profits on consumers. The slow (semi-annual) repricing of the cap has delayed the impact on consumer prices. Looking ahead, the UK government is introducing more frequent pricing of the cap (and there is talk of removing it altogether), but this will only affect the timing of changes in household energy costs – and the CPI – rather than their lasting level.

Another important cause of the divergent CPIs is the UK’s “fiscal shield” – or rather, its relative lack of one. Price caps, tax cuts and rebates have been used less here than in Europe.

The UK government’s modest contribution to household energy costs – which might cover 15% of this year’s anticipated bill increase – contrasts starkly with those in France, Spain and Portugal, for example, which have imposed stricter price caps. Average UK household energy bills are likely to have more than tripled in 2022, while in France electricity price increases are limited to 4% and gas prices capped at 2021 levels. While such caps keep the prices paid by consumers down, they are fiscally costly and risky over the long-term – they raise the prospect of shortages and of corporate failures if governments fail to adequately protect utility providers, exposed to volatile wholesale markets. Germany, for example, has already had to support its biggest utility company, Uniper.

Looking ahead, political pressure is mounting for the UK government to provide more explicit support, and this may well shape the outcome of the pending UK Conservative party leadership contest. In Europe, many governments have also introduced energy saving measures ahead of the looming winter gas squeeze: the UK government – whoever leads it – will be hoping not to have to do the same here.

From an inflation (and political) perspective, though the surge in energy costs is the most pressing concern, the trajectory of those core inflation rates matters most for the longer term. There is a gap between core inflation rates too: they are close to 6% (year-over-year) in the UK and US, and 4% in Europe, likely reflecting in part the relative strength of labour markets and ongoing wage pressures. So far, wages have not yet accelerated as sharply as they could have – but the UK’s labour market remains relatively tight, its inflation rate may continue to exceed Europe’s even when gas prices fall back.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.