Strategy blog: Peak house prices?

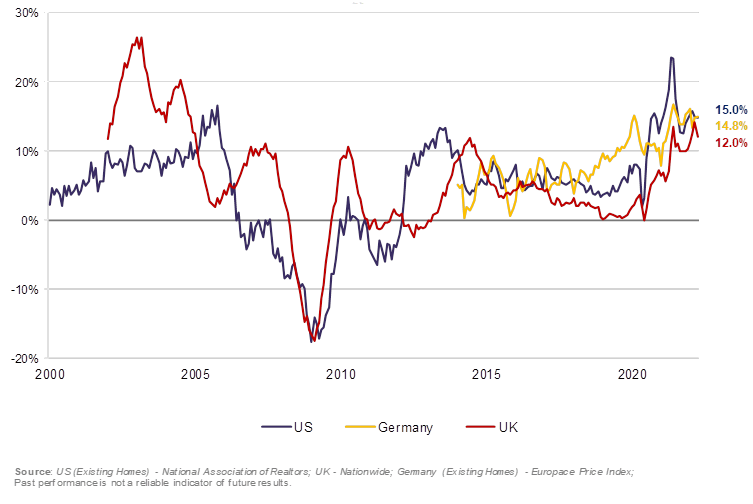

While most assets have weakened in the face of rising interest rates and geopolitical instability, one quasi-investment asset – property – has seemingly bucked the trend. A combination of pent-up demand, low mortgage rates and even lower inventory has pushed prices to new highs in many regions. As of April, US house prices were expanding at a 15% annual rate, while UK property prices have just seen their strongest pace of monthly gains since 2014 (+2.3% in May), expanding 12% since this time last year.

House prices (annual change, %)

With inflationary pressures persisting, ‘real’ assets such as property have clear appeal. But with interest rates rising, affordability deteriorating, and higher input costs weighing on new-build supply, there are some clear risks to consider as an investor.

Cyclical headwinds

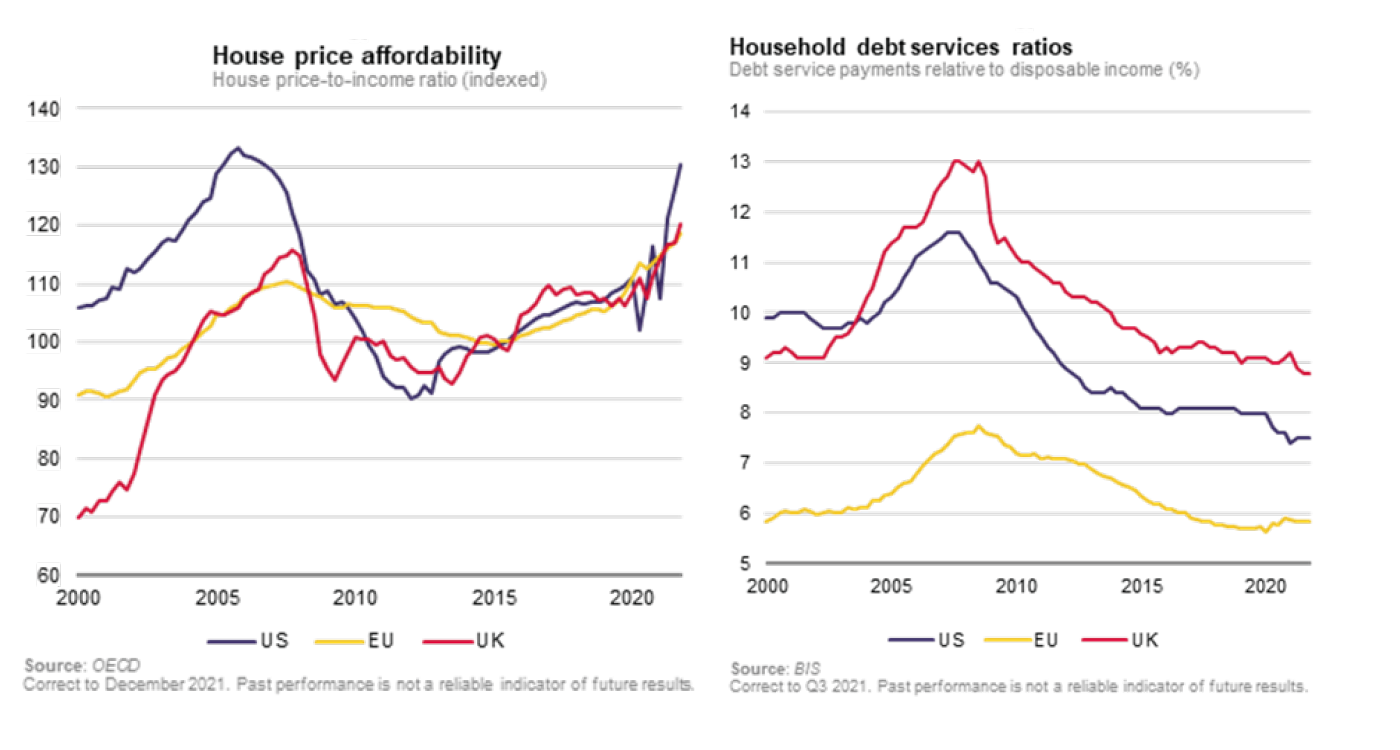

Undoubtedly, higher interest rates are the greatest threat to this property boom. Indeed, the cost of obtaining a 30-year US mortgage has nearly doubled since the start of last year – the current average rate of 5.3% is close to a 14-year high. In the UK, the equivalent 5-year fixed mortgage rate has moved from 1.3% to 2.4%. Even in Europe, where the ECB has yet to deliver on its increasingly less doveish outlook, banks are pre-emptively nudging fixed rates higher. Meanwhile, affordability has moved up the wall of worry; property prices relative to incomes have shifted firmly into ‘red’ territory – now at their highest ever levels according to the OECD.

Supply also remains under threat, with rising material and labour costs already weighing on construction activity. US residential housing permits have plateaued, albeit at elevated levels, while mortgage applications have fallen to a 2018 low. And while the stock of housing remains at historically low levels, if new developments fail to keep pace with demand – just as real disposable incomes and affordability get squeezed further - then wider caution may set in.

There is some evidence that this is already happening: US new home sales fell 17% last month: it can be a volatile and seasonal series, but an underlying downtrend is quite clear. Anecdotes paint an equally cautious outlook: only last year Zillow - the US property valuation platform – halted its expansion into renovating houses, citing expensive valuations and the challenge of rising costs and bottlenecks.

An unusual cycle

It seems unlikely that prices will continue to rise at their current pace. Yet, there is a distinction between stagnating prices and an outright collapse in prices (nor we would apply the over-used ‘bubble’ moniker in this context).

For one thing, those higher policy rates may not be immediately felt. The so-called transmission effect between interest rates and the real economy has been partially interrupted by the shift to long-term fixed rate mortgages. Higher interest rates may deter would-be-homeowners – and transactions will inevitably slow - but this won’t impact many individuals who have already taken advantage of historically low mortgage rates.

Affordability and inequality concerns may also ease as wages continue to grow, and that gap between incomes and house prices closes slowly. Equally, household debt servicing ratios - debt service payments relative to disposable income – are set to rise only very gradually from their historically low levels.

There is also a mix effect at play. Real estate is not one homogenous asset class, varying greatly by geography, sector and size (which is why we labelled it a “quasi” investment asset above). There is evidence that some pandemic trends have also started to reverse: depressed urban prices, for example, have started to accelerate faster (or less slowly) than their more rural counterparts. Meanwhile the disparity in different commercial property segments has narrowed – rental yields in depressed retail and (high quality) office space have moved lower, as post-pandemic footfall has picked up.

Conclusion

From an investment perspective, we’ve always felt that property scored well on strategic grounds: property is long-lived, its cash flows are relatively stable, and security of title is well-established. Overall, its duration, scarcity and tangibility offer the promise of real wealth preservation.

Of course, building a real estate portfolio is not without its challenges - liquidity and implementation considerations still apply. Direct ownership necessitates large, illiquid holdings – with maintenance to boot. Popular implementation vehicles, such as REITs – Real Estate Investment Trusts – have greater commonality with stocks than property. And the pitfalls encountered with ‘open-ended’ real estate funds are well-documented: the miraculous liquidity transformation that such vehicles offer can be illusory. That’s not to say real estate can’t offer a genuinely diversified, third source of return to stocks, but structuring, time horizon and manager expertise all matter in identifying opportunities.

More broadly, property is inherently cyclical: previous ‘boom and bust’ cycles have often exacerbated – even precipitated – economic slowdowns. The widespread use of leverage means that it has deep linkages with the financial system – the subprime collateralisation fiasco of the noughties serves as a painful reminder. However, while this property boom may start to subside, a moderation in prices now may not immediately present systemic risk. For lenders, the risk of higher defaults and loan impairments may be mitigated by greater financial prudence - tighter lending and affordability criteria - alongside a well-capitalised banking system. Put bluntly, banks do not seem to have behaved as recklessly in this cycle as they often have before.

For consumers, property plays an important psychological role – our home is often our biggest financial asset, and is seen as a long-term store of value. This perception of value matters – it can be an important behavioural driver of spending. While prices may soften, we do not expect a widespread rejection of the merits of ownership such as we saw (for example) after the frothier boom of the noughties.

Ready to begin your journey with us?

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.