Mosaique Insights - Issue 07

“Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall.”

This autumn many of us have seen a return from leisure to work. With the acquisition of Banque Pâris Bertrand in Geneva and the opening of a Wealth Management office in Madrid, it’s been all systems go. As we move into the year-end, we reflect on a year that, despite its obvious adversities from the Covid-19 Pandemic, has seen life start afresh.

With winter upon us and longer evenings ahead, we bring you our latest collection of insights and views on topics and strategies we think are important to you. We also include an interview with the head of the newly opened Madrid office, topical insights into the world of sports and sponsorship and a post-COP26 deep dive into the future of hydrogen in a world looking to move away from carbon.

As always, you can follow our latest series on our Wealth Insights page and should you wish to subscribe to any of our series, please do not hesitate to contact your client adviser.

Joyeuses fêtes, Frohe Festtage

Laurent Gagnebin

CEO, Rothschild & Co Bank AG

Dr. Carlos Mejia

Dr. Carlos Mejia

CIO, Rothschild & Co Bank AG

The following article is taken from the full client publication which was published on 07.12.2021.

Should you wish to receive the full publication, please contact your client adviser or send our Marketing team a message.

Excerpt

Kevin Gardiner, Global Investment Strategist

Kevin Gardiner, Global Investment Strategist

Inflation and the recovery

Is the world economy just running hot or could it be starting to overheat?

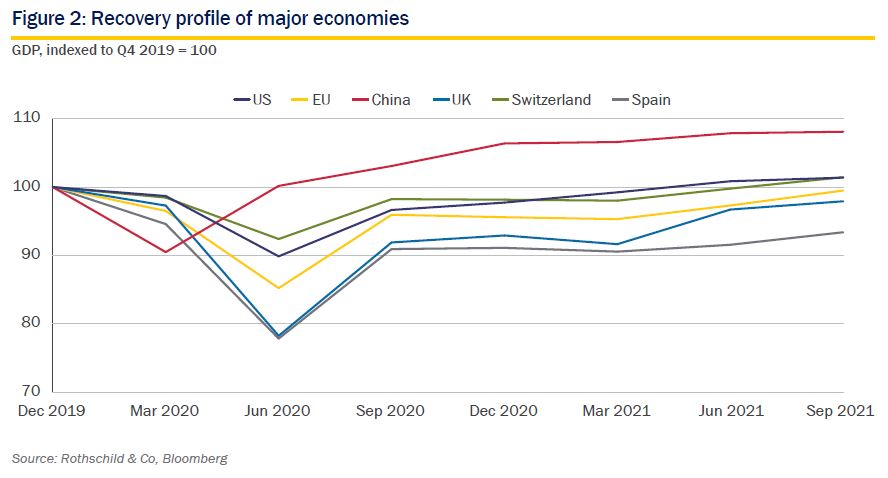

Just 18 months or so ago the economic headlines proclaimed mass unemployment. Today the talk is of labour shortages and inflation. It is not a big surprise. The dramatic slump in activity in 2020 did not reflect underlying economic weakness, but was a collective and considered response to the public health emergency.

We thought economies would be able to reopen quickly when it was deemed safe. When they did so, there would be pent-up demand, and policy would likely be overly generous. Inflation, not deflation, was always a likely eventual outcome. Virus permitting, this remains our view.

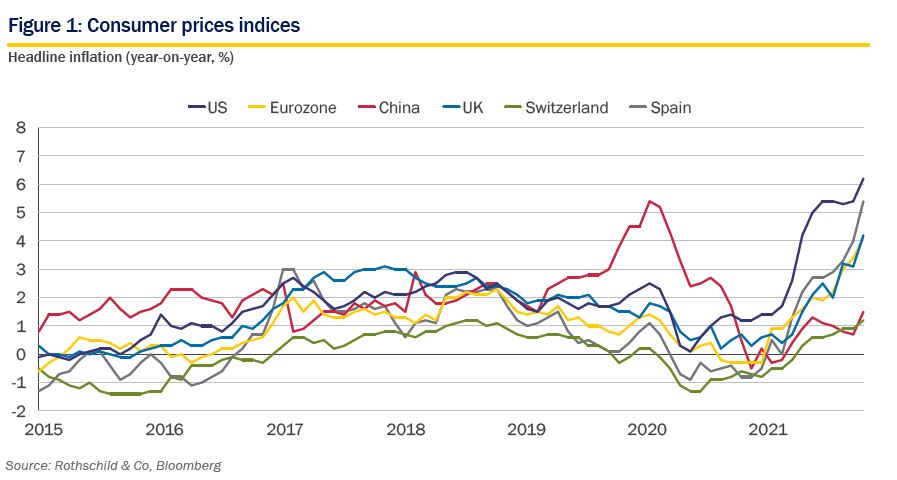

The spike in inflation to date has been bigger than we thought. In the US and Germany, headline rates have breached 6% and 4% respectively, remarkable levels (three-decade highs) by local standards. The inflation has so far been accompanied by ongoing growth: talk of “stagflation” is premature. The global economy is bigger than it was pre-pandemic, and business surveys remain upbeat. The main exceptions are where output is being held back not by weak demand, but by shortages of key inputs – including labour:wages are picking up alongside prices.

Some of these shortages may be with us for some time. The lead times on new semiconductor capacity, for example, are long, and semis are ubiquitous – the big carmakers are the most visible casualty. But many shortages reflect pandemic disruption, and may prove short-lived. And all the time, economic potential is expanding as productivity grows. New technology, and the learning curve, will together continue to give us more from less.

As bottlenecks fade, and some commodity prices stabilise or go into reverse, the immediate inflation surge will subside. We doubt that this will be the end of the matter, however. Some underlying inflation risk will persist, even as overall capacity grows, as long as demand remains robust.

Consumer balance sheets are strong and liquid, and politicians will be slow to push taxes up or cut public spending. Environmental mitigation and adaptation – signalled again in the Glasgow Climate pact – may also add (understandably, and unavoidably) to the inflationary mix.

The big central banks have clearly signalled their willingness to let economies “run hot” for a while. We get it: as noted, some of today’s inflation is indeed likely to be temporary, and is perhaps being overstated by the news industry (as was the deflation of spring 2020). We also recognise that economies may be less inflation

prone than they used to be. Labour markets are more flexible, economies are more digital, and monetary policy is more credible. Who would have guessed, for example, that Spain’s inflation could dip below Germany’s for a decade?

The risks are not symmetrical, however, and inflation may not be susceptible to fine tuning. It can get out of control and do serious societal damage: there are countless historical examples.There have been no hyperdeflations. And a careful analysis of the seemingly more benign inflation process requires taking many variables into account – such as, in the example above, Spain’s higher unemployment.

We think, then, that there is a significant risk that today’s “running hot” becomes tomorrow’s “overheating”.

We think, then, that there is a significant risk that today’s “running hot” becomes tomorrow’s “overheating”. In which case, monetary policy may yet end up tightening faster, and further, than central bankers and money markets expect.

Central banks in several smaller economies (and not just the usual suspects) have already begun to raise interest rates – getting their retaliation in first, perhaps.

We continue to think inflation will settle at a trend rate of perhaps 2% to 4% across the big developed economies. This is above the 1% to 2% pre-pandemic norm, but moderate rather than alarming. Higher inflation on this scale, and some interest rate risk, poses an obvious headwind for bonds. Prices have fallen modestly in 2021, but most high-quality yields remainbelow central bank inflation targets, never mind today’s above-target CPI rates.

It would be nice to think that such low real yields reflect our collective wish to value the welfare of future generations more highly. In reality, they likely reflect market technicalities, including liability-driven investing and central bank purchases. We doubt they will stay this low.

If this makes us sound like rather stale bond bears, that’s because we are. The future remains profoundly uncertain; diminishing marginal utility still applies to wealth as to most things; and corporate assets remain firmly profitable. Each of these argues for a positive long-term real discount rate.

Moderately higher inflation need not be a bad environment for equities. To date, corporate profits have been ahead in their tactical race with interest rates, and stocks have done well, even as inflation has revived. But if monetary credibility were at risk, and interest rate expectations were to change more dramatically, equities would be vulnerable too.

Stocks are the more volatile asset, even in normal times, and are currently expensive (albeit less so than bonds). And when investors need to liquidate assets in a hurry, they sell what they can, not what they should: blue chip equities can act as the cash-dispenser of choice in a crisis.

Our tactically overweight stance in global equities has served client portfolios well again in 2021, and can do so into 2022. When inflation is active, however, there is no iron law of wealth conservation, and we take nothing for granted.

Contact us

To read the full publication, please contact your client adviser or our Marketing team.