Wealth Management: Strategy blog – Carbon - a market price

Strategy team: Victor Balfour

Financial innovation conjures images of reckless activity, moral hazard and the relentless pursuit of profit. But occasionally, it can serve an important social purpose too. A case in point is the carbon credit market, which is once again gaining traction, as corporations increasingly look to shrink their environmental footprint.

A carbon credit is generic term for any tradable certificate representing the right to emit one tonne of carbon dioxide or equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG). One tonne is roughly equivalent to the average monthly CO₂ consumption of a US household.

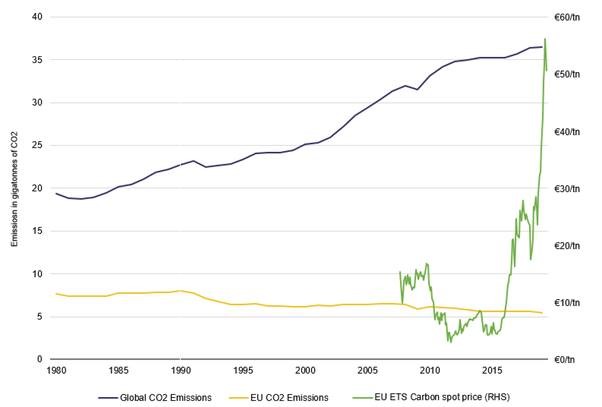

The current cost of polluting under the EU's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – the first international trading system for CO₂ emissions - has risen to an all-time high, briefly hitting €57/tn of CO2 in early July (up tenfold since 2017). This latest surge partly reflects the EU's ambitious Green New Deal (announced in September 2020) - targeting a 55% reduction in emissions (relative to 1990 levels) by 2030 – but it also reflects a shift in the corporate mindset too.

Annual CO2 emissions and carbon prices

Source: Our World in Data, Bloomberg

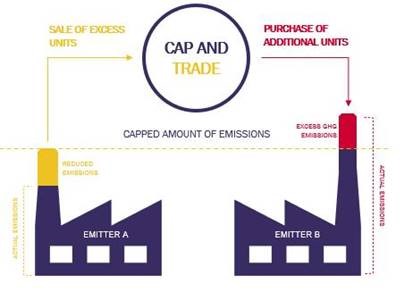

The compliance market

Carbon credits were around as an idea for some time but given practical impetus in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol - the first worldwide agreement to lower carbon emissions. GHG quotas were assigned to individual countries, and in turn, countries allocated 'credits' to regulated 'cap-and-trade' businesses – essentially polluting industries, such as miners and oil refineries. These credits would allow companies to emit a certain amount of carbon dioxide (or equivalent GHG), and most crucially, they are tradeable: unused allowances can be sold on the open market, while those companies in deficit can purchase additional credits.

Source: World Carbon Cap

Today many emissions trading schemes have been established to facilitate the objectives of the Kyoto Protocol, including the EU's ETS and the California Carbon Market. Specific Climate exchanges provide a spot market to trade such credits, and the broader derivatives markets - including futures and options – help to bolster liquidity, aid price discovery and allow businesses to hedge future emissions liabilities. At present, the deepest and most liquid contracts globally are those traded in euros on the European Climate Exchange.

The idea is a simple, but powerful one: by capturing what was previously a market "externality" – that is, a cost not reflected by the pricing mechanism, and so not taken into account in corporate decisions – the allocation of real resources can become more socially efficient, and in a decentralised way. Highly polluting and unprofitable enterprises that are unable to change their ways will see their true costs revealed and find it more difficult to secure capital. Industries that emit less carbon dioxide, or which can innovate and adapt their mode of operation, will flourish. As governments decide to reduce the number of credits over time, or if behaviour changes sufficiently, emissions in total might fall. At the very least, the true relative costs of doing business will be more accurately reflected in published accounts.

Beyond emissions trading, the Kyoto Protocol also established the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), enabling businesses to reduce emissions through offsets. These Certified Emission Reductions (CERs) create carbon credits by investing in areas such as renewable energy, tree planting or novel carbon capture techniques. However, going forwards ever tighter standards – particularly in the case of the EU's ETS - will likely prevent the use of such CER offsets for companies seeking to remain with their 'cap'.

The voluntary market

Increasingly the focus is turning towards the smaller voluntary carbon market, which co-exists alongside the regulated (compliance-checked) schemes mentioned above. Voluntary offsets enable environmentally conscious but non-regulated companies - and even individuals - to achieve carbon neutrality or in some cases even sequester carbon through offsets. Credits can be acquired directly from projects or from specific Carbon Funds or companies - recently, many banks and technology companies have been actively acquiring such offsets.

However, the area is a thorny one and mechanics of such voluntary credits are complicated.

Tough voluntary offsets are verified by independent third parties, their non-standardised characteristic prevents them from being used to fulfil obligations under the Kyoto CDM. This unregulated market isn't centralised and is much less clearly defined than the mandatory market, with a wide range in quality and cost. Take the example of a Brazilian farmer compensated for not felling his trees, against the development of a new hydroelectric power plant in Chile. Clearly the environmental benefits can vary tremendously.

Credibility has been improving in recent years, but 'greenwashing' remains a risk. Double counting has been evident and there is a surplus of questionable legacy credits now circulating. Perhaps most important is the concept of 'additionality'. There are many instances where carbon credits have been issued for projects that would have proceeded absent specific carbon funding.

A growth opportunity?

The carbon credit scheme is not without its critics and there are alternative approaches to reducing emissions. Some have suggested a simple carbon tax would be more effective, though this presents its own challenge in terms of harmonisation and incentivisation. Developing nations – some of the largest GHG emitters – are underrepresented, and the wider developed economy carbon markets are still patchy. The EU's ETS, for example, accounts for less than tenth of the world's emissions (40% of EU emissions) according to the World Bank.

Clearly, reduction (lower output of fossil-fuelled output) and substitution (using other forms of energy) are needed to achieve long-term emissions objectives. However, for some industries and technologies this may be impossible or uneconomical. The offset market allows polluting business to phase out their emissions without going ex-growth.

Looking ahead, the outdated Kyoto protocol is soon to be superseded by the Paris Climate Accord's objectives; Europe's compliance market is expanding, while free allowances (notably for European airlines) are being curtailed; and, most encouragingly, China has recently announced its own emissions trading market.

As for the unregulated voluntary market, demand is likely to surge in coming years as companies attempt to meet loftier Corporate Social Responsibility objectives. One estimate suggests that this segment, currently valued at $300m, will need to grow 100-fold by 2050 if countries and companies are to achieve net zero. Attempts to harmonise international verification standards - promoting transparency and simplicity – and the introduction of credible global carbon markets for such contracts will be crucial in reaching this objective.

Disclaimer

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.