Wealth Management: Strategy blog – A primer on SPACs

Strategy team: Kevin Gardiner and Charlie Hines

SPAC: A special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC; /spæk/)

SPACs are ‘shell companies’, formed for the purpose of raising cash through an IPO in order to fund an acquisition with the proceeds, within 2 years of its listing.

The SPAC structure for capital raising has garnered a lot of investor attention of late, with 2020 being touted the ‘year of the SPAC’; 219 SPACS raised $73bn in 2020, outpacing traditional IPOs ($67bn). Within the first two months of this year already, 128 SPACS have raised over $38bn – January alone surpassed the total raised in 2019.

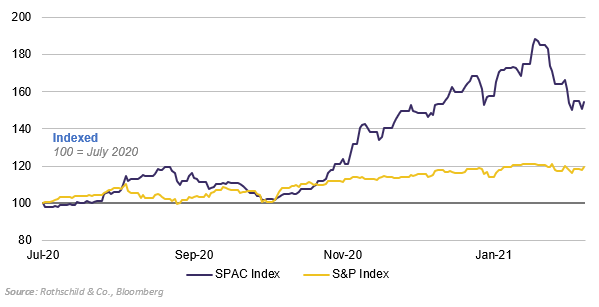

The price seems to reflect this. A SPAC Index – a benchmark that follows the aftermarket performance of a broad universe of SPACs – has risen more than three times as fast as the S&P since July 2020. Inevitably, this index has a limited track record (inception date July 2020), and smallish market cap ($27bn) and only represents a portion of the growing number of SPACS on the market.

Despite its in-vogue appeal – some celebrity investors have jumped on the bandwagon – there can also be genuine benefits to this type of structure. Firstly, given the shell companies’ lack of underlying operations (their ‘clean balance sheets’) the listing process is much less onerous than a traditional IPO – an entire SPAC IPO can be completed in as little as 15 weeks, reducing market risk and direct and indirect costs. Owners of target companies should face few nasty surprises – unexpected liabilities on the acquirer’s balance sheet – once the deal closes.

The SPAC model has appealed to private market sponsors too; partly because it provides a more liquid capital solution, but also because the sponsor retains a larger economic stake (20%) in the post-IPO SPAC, with lower upfront costs. This type of structure also allows them to go after larger targets in industries that traditional private equity documentation would normally prohibit. Structurally, as an equity funded vehicle, they require less leverage as well; SPACs provide equity capital without the debt servicing costs and covenants inherent in debt financing.

The structure does not come without its drawbacks, however. If a target is not found within two years of the SPAC’s listing, the cash is returned to the investor - the risk here being the opportunity cost of an investment forgone. More than 370 US SPACS have over $118bn in dry powder ready to be deployed. This risk in turn leads to others – too much capital chasing too few deals, inflated prices, or the acquisition of less desirable targets (to the detriment of the SPAC shareholder). In February of this year, a SPAC that initially targeted leisure companies announced a $200m deal with a biopharmaceutical company – no deal being worse, seemingly, than a bad deal.

Equally, SPAC investors have the right to exercise a redemption right once a transaction is announced, allowing them to exit if the acquisition turns out to be less desirable. Recent research has found that for a large majority of SPACs, post-merger share prices dropped, largely driven by share dilution – the need to raise additional funds through private placement, as well as cash redemptions. Either way, the SPAC investor bears these costs.

For now, the SPAC bandwagon is largely US-based, but there is increasing popularity for the structure in the European market as well. SPACs have actually been around for a long time in one form or another – ‘blank check’ companies date back to at least the 1980s, whilst the first SPAC was created in 1993, when blank check companies were prohibited in the US – which suggests that they aren’t going away anytime soon. There are obvious benefits when used in the right way; they can sit nicely beside traditional IPOs, but should not replace them entirely. Thorough due diligence and an understanding of what – and when – you’re buying is important, but then that is true of most investments.

The fact that the underlying investment is initially unknown seems troubling: we are all aware of the South Sea Bubble-era prospectus that offered “an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is”. But other funds can be similarly open-ended: we have noted elsewhere how hedge fund marketing literature can be remarkably un-specific, and private equity funds routinely open for subscriptions without knowing their prospective targets. The issue is a more subtle one, that of “good faith”: many SPACs may have it, whereas the South Sea venture likely didn’t.

That said, some investors need more transparency than others, and SPACs would not appeal to us as wealth managers until we knew what was in them.

We suspect the fashion for SPACs will cool in due course, and we doubt that it has materially affected the trajectory of the wider stock market. Nor do the amounts involved seem big enough to pose a systemic financial risk – even if SPAC investors themselves should turn out to be using borrowed money to buy them. For perspective, the market capitalisation of the S&P 500 is $34 trillion.

Disclaimer

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.