Wealth Management: Strategy blog – Corporate debt hangover

Strategy team: Victor Balfour

For most of the past decade we have been reading a lot about the impending collapse of corporate credit. And if there was ever a year for chickens coming home to roost, a global pandemic seems a likely catalyst.

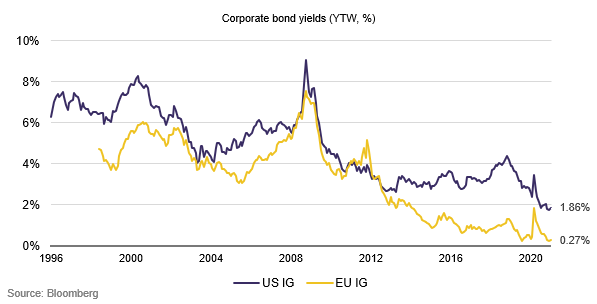

However, the projected surge in bankruptcies and defaults has (so far) failed to materialise. It seems the passage of even lower interest rates and the enduring promise of deeply supportive policy has proven to be a boon for corporate issuers - borrowing costs have fallen to all-time lows.

Indeed, the rate of debt accumulation in 2020 is on track to be the fastest since the Global Financial Crisis (for US non-financial corporates); outstanding liabilities currently stand at $11tn – nearly double the level witnessed towards the end of the last cycle and now over half of US GDP.

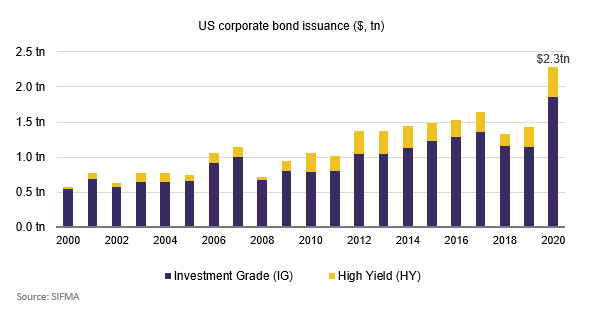

In contrast to recent years, the torrent of corporate fundraising this past year and into 2021 was most visible in public debt markets – alongside a resurgent M&A market. US corporate bond issuance (which forms a growing share of that overall corporate debt picture) recording its strongest ever year, with many recent issues oversubscribed.

Naturally, questions are mounting once again. Are corporations borrowing too much? Is this another sign of ‘bubble trouble’?

Though the absolute level of debt may be worrying, the ‘bubble’ moniker – often too casually applied in our view - is likely misplaced here.

The decision to issue debt is shaped by many things, including internal cash flow, the level of interest rates, equity valuations, and liquidity. Total liabilities viewed in isolation tell you nothing about the ability of a company to repay or service those debts. And if a robust economic recovery lies ahead, and earnings rebound, leverage may not be so troubling.

2020: a year of two halves

Last spring was characterised by corporate distress: thin liquidity, widening credit spreads and many companies forced to fully draw on their credit lines. The divergence in the second half of the year was pronounced: liquidity was abundant and financial conditions loose. At the centre of this effort was the US Federal Reserve’s numerous crisis fighting facilities, including programmes that directly purchased commercial paper and high-quality corporate bonds (and later expanded to even recently downgraded ‘junk’ rated issues). This extension of this ‘lender of last resort’ function more than reversed the brief spike in borrowing costs, with high quality corporate credit yields (and yield spreads relative to government bonds) now at (or near) all-time lows.

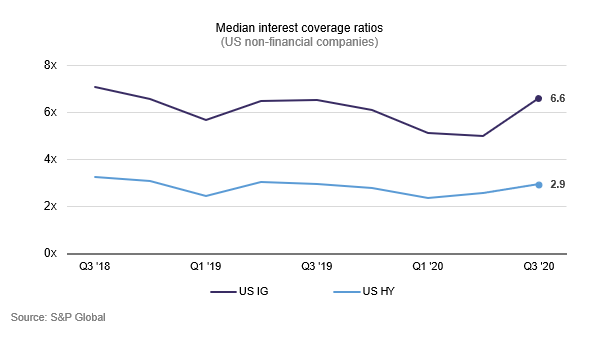

Despite the surge in the overall stock of debt outstanding, bottom-up analyses reveals that debt servicing burdens are also starting to fall once again: interest coverage ratios (profits before interest and taxes relative to debt service costs, the inverse of the servicing burden) for high quality borrowers at the end of Q3 was 6.6x - higher than it was at the end of 2018.

At the same time, those corporates are even less exposed to the (modest, at present) risk of rising interest rates – the maturity profile of their debt continues to extend. Fundamentally, and almost paradoxically, the average US company is in a better position to service its debts than before the crisis.

An uneven recovery

While many companies have been forced to issue debt to recapitalise their deteriorating balance sheets, many fundamentally sound companies have simply issued it to take advantage of even lower rates. This might be a sensible capital allocation decision.

Unsurprisingly, technology and healthcare companies have been the major opportunistic issuers, but other sectors, including many industrial and service businesses with strong fundamentals, have also been favoured by investors. Meanwhile, for companies in the travel and retail segments, borrowing costs (and spreads) remain elevated, reflecting their more challenging outlook

Looking across the credit spectrum as a whole, one side effect of the policy backstop, coupled with investors’ ‘hunt for yield’ (aka TINA – ‘There Is No Alternative), is that riskier borrowers have been able to issue debt more easily. The ballooning BBB segment (one rung above speculative grade) - a trend that was in place before the pandemic - has continued as many highly rated firms have adopted more aggressive financial positions.

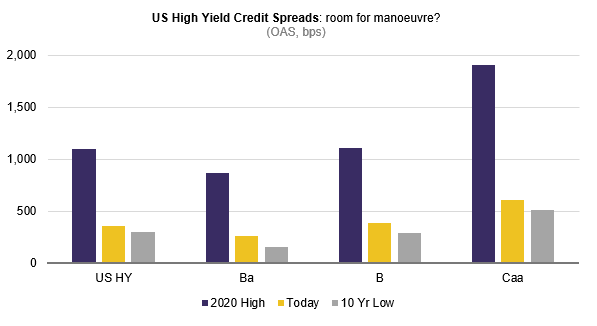

While this segment now represents more than half of the US investment grade universe, downgrades and the surge in ‘fallen angels’ have been less dramatic than feared. The same applies to defaults: the trailing 12m default rate for US high yield borrowers stood at 6.6% in December – elevated, but not outlandish. This figure may drift higher in the months ahead – if supportive policies are withdrawn before recovery is stronger - but it could yet be a relatively mild outturn compared with previous recessionary default cycles, when peaks ranged from 10-13%. This may partly explain why even the riskiest bonds have seen their spreads compress to pre-crisis levels:

Of course, investors attracted to the yield on speculative bonds need to be mindful of the further erosion in creditor protections – what few covenants remain are gradually being weakened.

Looking ahead to 2021

There is a clear cyclical pattern to leverage: credit accumulation occurs as economic activity accelerates, and deleveraging typically occurs following an economic shock. This crisis – and the unprecedented policy response – has upended (at least temporarily) that relationship: companies have been able to borrow unencumbered even as cash flows receded. Though some indebted sectors and companies may well face a reckoning, the prospect of a faster and more even recovery may prevent those gloomy predictions from become reality.

After 2020’s borrowing surge, it seems likely that debt growth will slow; the recovery in corporate profits and cash flows will likely depress the need for another surge in issuance. Though this doesn’t presage the start of a deleveraging cycle, with benchmark government yields either close to zero, or in negative territory in many countries, spreads may not rise far soon.

Naturally, the risk to investors is that the scope for further gains is somewhat constrained and given the low starting level of yields, we are increasingly confronted with the possibility that holders of both investment grade and even high yield issues may no longer be able to generate returns in excess of inflation. This, rather than more dramatic collapse (or the bursting of a “bubble”), is what we think likely looms ahead for corporate bonds.

Disclaimer

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and nothing in this blog constitutes advice. Although the information and data herein are obtained from sources believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of fraud, no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by Rothschild & Co Wealth Management UK Limited as to or in relation to the fairness, accuracy or completeness of this document or the information forming the basis of this document or for any reliance placed on this document by any person whatsoever. In particular, no representation or warranty is given as to the achievement or reasonableness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in this document. Furthermore, all opinions and data used in this document are subject to change without prior notice.