Wealth Management: Market Perspective – What will we leave behind? – The kids are alright

Kevin Gardiner, Global Investment Strategist, Wealth Management

“On what principle is it that, when we see nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?” - Macaulay (1830)

A discussion on the theme of succession and stewardship got us thinking about some wider economic issues. We talk a lot about the sorts of individual portfolios that will best allow investors' nest eggs to be passed on intact to future generations. But collectively, what sort of world will we be leaving behind us?

Received wisdom is not optimistic. On top of the short-term cyclical issues usually discussed here - including geopolitical tensions, tariff tussles, strained EU relations, an increasingly mature business cycle and some rather elevated bond and credit prices - we find investors worrying about several longer-term, structural and even existential themes.

We suspect the worries are overdone. Just as we are better off than our parents, our children will likely be better off than us.

We tackled one of those concerns, debt, in February. In addition to worries about what it might mean for today's economy, some very smart people have also suggested that we are somehow borrowing from future generations. Collectively, however, we can no more borrow from the future than we can borrow from Mars.

We've also discussed the related theme of secular stagnation often in these pages. With unemployment in the US, UK, Germany and Japan at generational lows, and trends in developed world corporate profitability close to 50-year highs, the identified shortfalls in measured output growth may not be as meaningful as pundits like to suppose. The diagnosis is arguably a wise-after-the-event explanation of the GFC and its aftermath offered by an embarrassed economic establishment.

Some of the other concerns are more difficult to dismiss. The environmental challenge is real, and seems alarming. New technology, and the prospect of artificial intelligence (AI), can be daunting. And amid today's fast and furious political debate, some important societal lessons are being forgotten.

The pale blue dot

It's an old and intuitive idea: we are using up the world's scarce resources. How can Carl Sagan's pale blue dot possibly sustain us for long? More recently, the worry has broadened into an awareness that we may also be causing a catastrophic change in its climate.

Click the image to enlarge

In practice, however, our ability to measure accurately how much food, water, oil and metal we have left is not what we think it is - and to date we have erred on the side of underestimating them.When Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, warning that the world would be unable to feed itself, there were around one billion people on the planet. There are now seven billion. Famines sadly do happen, but they reflect local failures - of fertility, weather, or government - rather than a global shortage.

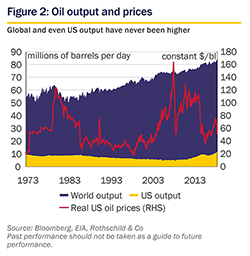

Writing in 1956, the geophysicist M. King Hubbert predicted that US oil output would peak in the early 1970s - which it did, before shale extraction lifted it to today's record levels. In 2001, Professor Kenneth Deffeyes predicted that global oil production would peak in the next decade: it too is currently at record levels.

Click the image to enlarge

In 1980, the US economist Julian Simon challenged the pessimistic environmentalist Paul Ehrlich to a public wager. Despite Ehrlich's claim of encroaching depletion, Simon bet that the inflation-adjusted prices of a list of five commodities - to be chosen by Ehrlich - were more likely to fall than rise over the following 10-year period. This was a brave call: 10 years is a short period in this context, and all sorts of things could have boosted prices, even if Simon's underlying diagnosis were true. But as it happened, the prices of all five metals chosen by Ehrlich fell over the period, and he duly wrote the cheque (see Paul Sabin's The Bet).Generally, we have too little confidence in innovation and the price mechanism. We live on the wafer-thin surface of that pale blue dot, and can only guess at exactly what lies in and beneath it. Exploration and extraction techniques are evolving, and when scarcity does prevail, higher prices can spur further efforts, and boost recycling (where feasible) and the use of substitutes. Two-thirds of that surface is water - and may become more available to us as desalination processes improve.

Further climate change is unavoidable, and attempts at limiting its extent have not been helped by America's withdrawal from the UN Paris Climate Accord. Nonetheless, there is still room for mitigation, adjustment - and perspective.

Arranging intergovernmental action is like herding cats, but it can be done: emissions of CFC gases were taken in hand several decades ago. Bringing 'externalities' into the realm of markets - as with carbon trading - can help. So too can the development of renewable and non-carbon-based fuels, including, perhaps, a revival of interest in nuclear fission (and maybe, one day, fusion).

It sounds defeatist to talk of adjustment, but mitigation is not costless: it may make more sense to learn to live with much of the further climate change ahead. Cold weather kills more people than hot; some regions will become more fertile; higher sea levels, and more disruptive weather - which has not yet arrived - can be planned for.

Similarly, we have to ask - feelings run high here - if there are other, less stark, perspectives out there. The prospective increase in average temperature is small by comparison to the existing variation across regions.

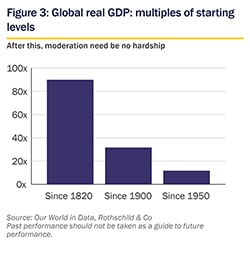

Click the image to enlarge

After the rapid ascent in living standards in the last 200 years (figure 3 above), some mitigating moderation in growth in the decades ahead would hardly be catastrophic; and one of the byproducts of the current low-interest rate regime is that we are already implicitly valuing the welfare of future generations more highly than ever before. The low discount rates used in the Stern Review in 2006 no longer look quite so outlandish.

Finally, and at the risk of stating the obvious, to suggest the earth's resources may be more sustainable than feared does not mean we should not care for the environment. Similarly, climate change may not be an existential threat, but we might still hope and vote to mitigate its effects.

The singularity

The robots are coming, and with them the moment when AI matches and surpasses our own - the so-called 'singularity'. At least, that's what we're told.The Bank of England's chief economist warned in 2015 that 15 million UK jobs could be taken by robots (there are currently 24 million full-time jobs in the UK, the most ever, and 1 million more than when he made the comment). Professor Stephen Hawking warned in 2014 that AI could result in the end of the human race. The 'paperclip maximizer' is reportedly set to turn the world into a stationery cupboard.

But we see new technology as the creator, not destroyer, of long-term prosperity. It makes us more efficient, more capable, healthier and happier - and helps us obtain more of those scarce resources. And we suspect that genuine AI is still some way away. The room for robots to replace people rather than serve them can be overstated.

Unease is understandable: new technology can also be disruptive. Processing jobs - in finance and legal services now, for example, as well as in factories - are vulnerable, and the Luddites, remember, did lose theirs. We need a decent safety net and retraining for those of us who are displaced. However, new industries and occupations will help fill the gaps - though we never know beforehand what they will be - and historically, the adoption of new technology has been associated with rising overall living standards.

Processing jobs are not the only ones. Financial services, for example, are not just about data-mining, trading and settlement, but also involve the provision of advice, connections, and yes - occasionally - even service. The big questions we face tend to be conceptual, about causality rather than correlation, and are not easily answered - by us, or machines.

For example: what really drives interest and exchange rates? Is a price-earnings (PE) ratio of 16 too high? Will investors fund a new issue? Does a merger make commercial sense? Can we insure against catastrophe? What is a 'true and fair' picture of a company's health? How might we best safeguard the real value of our savings?

Other service sectors also face questions - and/or involve genuine customer engagement - that cannot be covered by pushing more computing power at them.

Meanwhile, there are still many physical tasks that even the most dexterous and agile robots will not be able to do any time soon. This may trigger some interesting shifts in real pay: carers and construction workers, for example, may do better relative to many production and clerical workers. Plumbers and Premier League footballers may get even more expensive.

What about that bigger claim made for machines - that they are on the brink of independent thought and consciousness?

We are sceptical. Computers crunch lots of numbers, and identify patterns, very quickly. But they don't think - and they don't create: they copy, from examples we've shown them. If they are to start thinking and creating, they will have to become conscious, and start acting independently, spontaneously. This seems unlikely any time soon.

We don't know how our own minds work, so we can hardly program consciousness into machines. Indeed, what we do know is that whatever it is that underpins intelligence, it is not a single, complete and watertight system of logic or language. Such a system cannot exist (Kurt Godel demonstrated this in 1931).

The various languages at our disposal are all unavoidably incomplete or inconsistent. Suppose I write that I am a liar - do you believe me? Or consider (as Bertrand Russell did) the set of all sets which do not contain themselves as members: does it contain itself? Nonetheless, we are able to communicate and function - we somehow recognise that different contexts require different languages and work-arounds. But we don't know how we shift our frames of reference accordingly, let alone how we might instruct a computer to do so.

It's not just the human mind that has us baffled. Other organic intelligences - starlings, fish, termites - display uncanny capabilities that are currently beyond our understanding.

For now, then, the 'A' in 'AI' may variously stand for artificial, autonomous or augmented, but the 'I' - intelligence - is missing. The questions we ask machines to answer have to be chosen carefully if the answer is to be usable. In The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, remember, the computer Deep Thought was asked for “the answer to life, the universe and everything”. After 7.5 million years, Deep Thought concluded that the answer was 42.

If none of this convinces you, just consider this: if robots are going to do everybody's job, who will buy the stuff they make? As Henry Ford said, it's not a good idea to sack your customers.

In this Market Perspective:

Foreword

What will we leave behind? (current page)

Political Pendulum

Economy and markets: background

Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (PDF 1.6 MB)

Listen to the latest Market Perspective Podcast