Wealth Management: Market Perspective – We'll meet again

Kevin Gardiner, Global Investment Strategist, Wealth Management

A dramatic downturn, but how long will it last?

The superlatives are mounting. This downturn is already the fastest, the first to be deliberately engineered, and the least contentious (we all agree what is occurring and why).

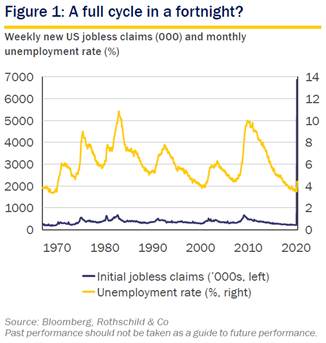

We have seen a full cycle's US unemployment claims (22 million) compressed into four weeks' data. Looking ahead, double-digit declines - on a non-annualised basis - in GDP and corporate earnings (EPS) are plausible. Arithmetically, one saving grace may be that the lockdowns' centre of gravity straddles two quarters.

It is tempting to hope that monetary and fiscal support may avert it, but this might be to miss the point. The authorities have acted with unparalleled speed and scale, having learned from 2008 (and in turn from the 1930s), but they cannot - and are not trying to - stop economies shrinking. Instead, they want to reduce the longterm damage and suffering that closing much of the economy will cause. Some businesses inevitably will fall between the cracks. Sadly, the poorest families will suffer most, as always.

For now, we would not worry about the public cost of those measures. We don't know how much support will be taken up. Bond markets are telling governments that funds are available. The idea that we are borrowing from future generations is fallacious. There is also the possibility - and reality, as quantitative easing (QE) is revived and expanded, and day-to-day central bank financing rises - of money printing, though we see that as riskier. Systemic financial risks may also be manageable. Bank capital was rebuilt - more so in the US and UK than in the eurozone - and loan growth was subdued in this cycle. Interest rates are low in real as well as nominal terms.

The downturn suddenly upon us is big, then. But to draw comparisons so quickly with the Depression - as many pundits are - is mistaken as well as tactless. The misery then - to which The Grapes of Wrath is a better guide than economics texts - lasted for years. Living standards now, even at their looming lows, and for the poorest, are much higher.

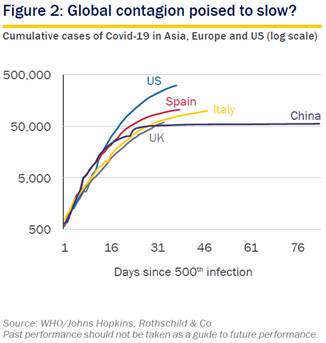

The reaction to COVID-19 has been so much more dramatic than we'd thought, but we still think the worst disruption might not last long. China's timeline - and there has not yet been a big second wave - may still be appropriate. Italy and Spain may be following a similar path, for example.

Moreover, public resolve may weaken, and lockdowns loosen, even if contagion doesn't slow sharply. The loudest dissenting voices so far have said that governments should have done more, sooner. There is now more public discussion of:

- The distinction between science, and the mathematical modelling of complex systems (in which small changes in key variables deliver very different outcomes).

- The intergenerational and societal fairness of tackling the illness in this way (the young and poor bear the biggest costs).

- The big, certain, and possibly unsustainable, costs of suppression.

- The fact that society routinely faces difficult life-changing decisions, including those involving healthcare.

- Whether Sweden's alternative approach - supported by a population that favours bigger government - is sustainable (internationally, as well as domestically).

- Possible exit routes.

Click the image to enlarge

What sort of economic revival?

Usually the constraints are confidence and spending power. Now, the immediate constraint is dictat. When controls are relaxed, much business will resume.

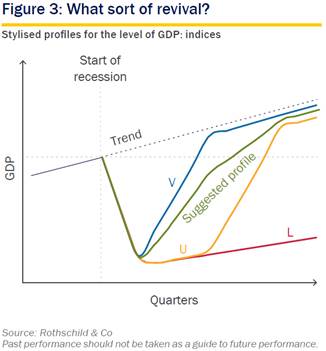

Precision now - in either direction - is spurious. We think the precipitous drop may be followed immediately by some rebound. If policy stays expansionary, a return not just to the starting point, but eventually to the trendline we might otherwise have followed is feasible. We do not think long-term growth rates need be lower. Overall, a lop-sided V or “swoosh” profile seems likely: the rebound will take longer than the fall, as some businesses will fail.

Even when/if economies return to their earlier trajectory, some lasting damage to aggregate incomes will have been done: the area between recovery and the trendline in figure 3 will be painfully positive (more so for balance sheets, as bankruptcies and stranded assets drive a wedge between the path of GDP and capital).

Capital markets will however likely focus first on the direction of travel, not distance or speed.

Where does this leave stock markets?

Stock markets' response looks more understandable given the scale of suppression. That said, we thought they overestimated the long-term loss of business, and still do, even after their partial rebound. Losing even a full year's earnings would destroy only a few percentage points of market value.

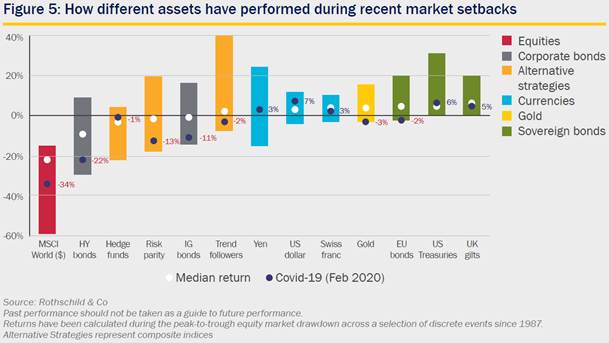

We've seen the fastest-ever bear and bull markets. On 23rd March the MSCI all-countries index in dollar terms had fallen by 34% since mid-February's high. It has subsequently rallied by 22%, to stand “only” 19% below the peak.

We may yet see a new low. But the idea that “lows” are always revisited before recovery” is as fallible as other market lore. Arguably the 23rd March low was itself part of a “revisiting” process.

Corporate earnings are set to slump for a while, and dividends have already been cut, making it (even) more difficult to value stocks. We'd focus on cyclically adjusted PE ratios and maybe price/ book ratios. They suggest stocks were more expensive than usual in January, but having fallen back below it are now at trend (that is, they are not clearly “cheap”). Metrics that take interest rates into account - such as discounted cashflow - do make stocks look cheap, but are more contentious.

Valuations are less likely (at least, not unless they fall drastically further first) to trigger a rebound than news on contagion and lockdowns.

Click the image to enlarge

Where can investors hide?What sort of assets can diversify equity risk, and how have they fared so far? Most assets are less volatile than stocks. In balanced portfolios, we look for assets with complementary characteristics: uncorrelated (or negatively correlated) performance that might deliver positive returns - or at least losslimiting stability - when stock markets fall. Traditional diversifiers include bonds, gold, and cash (the latter is easily overlooked: it has no yield, but is stable). Newly popular, “alternative” assets include derivatives, structured products and (some) hedge funds, and private markets (equity and debt). Click the image to enlarge The turbulent first quarter exposed the inconstancy of some correlations. It also reminds us that the apparent stability of the private markets reflects their illiquidity - they do not trade often, and so we can't know how they did. Figure 5 shows that while US Treasuries and UK gilts delivered positive returns, with their yields hitting new lows, eurozone government bonds fell (Italian bonds weakened, and gains in Germany and France were small). Performance generally has fallen short of that in other recent stock sell-offs. For each percentage point of stock market decline, bonds delivered less than “usual”. For investment-grade (IG) corporate bonds, the difference is big. They are never as safe as government bonds, but their fall in value here is pronounced, and their liquidity (not shown) has evaporated. Their extra yield has been costly in terms of mark-to-market volatility and illiquidity. Lower-grade, speculative - “junk” or “high yield” (HY) - bonds have also fared poorly, though these are always risk assets. At first sight, the failure of bonds to do better is surprising. The stock sell-off is accompanied by major economic disruption and expanded bond-buying by central banks, and the low initial level of yields has increased their price sensitivity (their “duration”). However, in Europe in particular, those low starting yields may have proven a deterrent. If investors believe yields simply can't fall much further (remember they are already negative for the most creditworthy countries), they will be reluctant to bid even more for them. With policy rates staying even lower for even longer, little inflation (yet) and ongoing central bank buying, bonds may stay expensive. But they may at last be running out of headroom - which is why we've held few of them ourselves. Other diversifying assets have also underwhelmed so far. Gold has not glittered as it might have; hedge funds remain lacklustre; and bitcoin (not shown) fell sharply. Safe-haven currencies have done well, but not compared to the scale of equity risk. Humble cash at least has done what it usually does: maintained its nominal value. With inflation low, it is one diversifier whose real performance - despite lack of yield - may have improved. Another would be derivativebased strategies involving put options, particularly given how cheap they were, but such bespoke assets cannot be shown. Mitigating stock market risk is getting harder. With interest rates so low, there may simply be fewer safe havens. |

Click here to continue: Longer-term uncertainties

In this Market Perspective:

- Foreword

- We'll meet again (current page)

- Longer-term uncertainties

- Economy and markets: background

- Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (PDF 1.1 MB)