Market Perspective – Growth insurance - or inflation pass?

If looser policy is the answer, what's the question?

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

John Maynard Keynes

Growth fears resurface (again)…

The big news since the last Market Perspective is the collapse, in early May, of the US-China trade truce. Stock prices - fresh from a remarkably strong April that saw the S&P 500 celebrating a new all-time high - promptly reversed, while safe-haven bonds - already expensive - surged further.

The fear is that a trade war will hit a global economy - and an elderly US business cycle - that has already lost momentum, turning a slowdown into something more serious.

Meanwhile, risk appetite has also been hit by the revived chances of the UK leaving the EU without a deal; the Italian government's budgetary misbehaviour; and an escalation in Middle East tensions. Global business surveys are showing falling confidence, and the pundits who have spent the last 10 years waiting for the double dip are sharpening their pens.

But the revival in volatility has in fact been relatively muted, at least so far, partly because central banks have gone out of their way to reassure markets that monetary policy will (try to) soften any macroeconomic blow. And while we don't know exactly what their reasons are, one of them must surely be the continuing stability - verging on dormancy - of inflation.

…and central banks have a rethink

Cutting interest rates in a fully employed US economy would look a little unusual in 'normal' times. Admittedly, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has two tasks: to keep inflation low, but also to keep employment high. And it could be that the Fed thinks risks to employment have indeed risen sharply with the latest trade tussle. The starting point, however, is one in which the US unemployment rate is at a 50-year low, a point at which we would usually expect inflation risk to be intensifying. We associate low unemployment with higher inflation - a relationship known as the 'Phillips curve', after the professor who first plotted it.

It is unlikely the Fed would encourage investors to expect lower rates - which is what money markets are now doing, and quite confidently - if they thought faster inflation was likely. Specifically, we doubt it has changed its mind (until December, remember, it was raising rates) simply because it is being intimidated by the markets and media - or the President.

Either it has become markedly more pessimistic about growth and employment in the second half of the year, or is having a rethink about how inflation works, or both. Note that the Fed's targeted measure of inflation, at 1.5% in April, is below its working objective of 2%, but hardly materially.

The Fed is by far the most important central bank for investors, and its U-turn - or pending U-turn - is the most dramatic. But the European Central Bank (ECB) has also signalled a looser stance, suggesting it is actively considering cutting interest rates further “if necessary”.

Eurozone unemployment is twice as high as in the US, and the ECB's mandate is narrower (inflation only) and less precise (a rate of inflation “below, but close to, 2%”). But unemployment has rarely been lower in the euro's lifetime. While the inflation rate, at 1.2% in April, is below target, the gap is not big. As noted, the target is imprecise to begin with.

Again, we conclude that the ECB sees looming bad news on growth sufficient to materially reduce inflation via Phillips-curve type links, and/or it is also having a rethink on the way the economy works. And where the ECB goes, so too will the Swiss National Bank - it closely shadows ECB policy so as to try to avoid destabilising currency flows.

The Bank of England has effectively been sitting on its hands in the face of the perceived economic risks associated with the UK's secession from the EU. It does have an informal mandate to assist the real economy, as well as a formal inflation target of 2%. With UK unemployment at its lowest since 1974 and inflation at target, there has been no case for easier policy here either - but that may not stop it following any Fed or ECB lead.

Slaves of defunct economists?

Growth expectations have taken a knock, but we suspect - as noted - there may be a bit more to this monetary rethink. Because this is not the first time in recent years that inflation and interest rates have turned out, for some reason or other, to be staying “lower for longer”. Bond markets recently show a small but distinct fall in US and eurozone inflation expectations, independent of growth expectations.

We have always seen inflation risk and monetary normalisation as the most likely cyclical clouds to emerge in an otherwise relatively clear macroeconomic sky, but they have just not materialised yet (again). US wages have failed to break significantly higher in that fully employed labour market, and now the Fed, which was at least heading in the long-expected direction from late 2015, has - as noted - seemingly stopped short of its previously signalled destination.

Those inflation targets are not there because a bit of inflation is a good thing. They are there because inflation was once public enemy number one, and after experimenting unsuccessfully with various frameworks to tackle it - including demand management, monetarism, income and exchange rate polices - it was decided (by the Bank of New Zealand, initially, in 1990) to adopt a formal target as a way of capping the self-perpetuating expectations that created a 'going rate' mentality. The (arbitrary) target itself was the key - exactly which levers were to be pulled in pursuit of it was not so important (other than that they were broadly credible).

Inflation-targeting central banks have certainly presided over lower inflation, though we can't be sure that it was the regime, rather than circumstance, which was responsible.

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 1 shows how far we've come in the last 40 years. 1979 may not mark the peak in inflation, but it does mark a realisation in both the US and the UK that something dramatic had to be done about it.

In fact, as figure 1 shows, the major decline in inflation was already behind us by the millennium, since when it has been broadly stable. Even in Japan - where deflation has been much smaller than popularly imagined - it has been broadly flat for 20 years.

Nonetheless, inflation continues to cast a long shadow. The idea that stronger growth would cause higher inflation has remained central to the economic debate. Its abeyance could, for much of the time, be explained by unemployment - until now.

The Phillips curve was intuitive - if you subscribed, as many of us did, to a particular way of looking at the economy, a worldview taught unthinkingly at most faculties. This establishment approach is largely Keynesian* (which is ironic given his comment about defunct economists quoted above), but many monetarists implicitly subscribe to it too.

But there is an alternative viewpoint - one in which the link between growth and inflation might even run in the opposite direction.

*Keynesian economics (also called Keynesianism) describes the theories of British economist John Maynard Keynes. He advocated for increased government expenditure and lower taxes to stimulate demand.

A non-establishment view of growth

The establishment view focuses on the demand side of the economy. It sees consumer, business and government spending as the main drivers of growth, and it dates from the Keynesian revolution which shaped post-war economic policy and measurement (national accounts - GDP itself - were largely compiled with the Keynesian framework in mind).

It is easy to imagine how an uptick in confidence ('animal spirits') can encourage businesses or households to spend more, and call forth more output. Supply is viewed as largely passive - the most visible exceptions being when it has been suddenly reduced, as (for example) when oil supplies have been interrupted, or when industrial relations have been disruptive.

A focus on excessive aggregate demand - the result of animal spirits, loose monetary policy or interrupted supply - lends itself naturally to imagining 'too much money chasing too few goods' (or too few workers), with inflation as the result.

And this is still the default setting for macro debate, even in the disinflationary era. You can see it in talk of a 'savings glut' and 'secular stagnation', where the implicit assumption is that demand is not strong enough to make economies grow faster. Monetarists who focus on slow growth in the money supply are also implicitly placing demand first.

An alternative view is one in which aggregate supply, not demand, routinely sets the pace of growth. It is hard to imagine supply increasing independently - but it can, and it has. And if growth is led from the supply side, then deflation, not inflation, is a more intuitive outcome - a sort of 'too many goods chasing too little money' type situation. And the faster the supply-led growth, the bigger the deflationary tendency.

In the demand-led establishment view, Global Inc is effectively a factory waiting for customers to arrive to get the production line moving. In the supply-side view, Global Inc is producing even before the customers arrive.

It sounds far-fetched, but it can happen. Before the Keynesian revolution - which was fostered, remember, by the special weakness of demand in the Great Depression - economists viewed aggregate supply and demand more evenly. Of course, in measurement terms, what is spent and what is produced add up to the same thing - we just don't know from which side the motive force comes.

Supply-driven growth happens when productive potential increases. And such windfalls may not be as rare as we might think. New factories don't appear overnight. But new resources - and new technologies - do.

Back to the future?

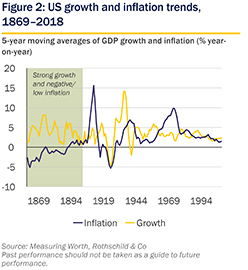

A clear example of supply-driven growth was in the US in the second half of the 19th century. A newly unified federal government presided over an increasingly connected economy in which the infrastructure was improving steadily and in which technology was evolving in leaps and bounds. The resultant surge in supply-side efficiency - a wave of productivity growth - saw sustained strong growth in output alongside a price level that was falling more often than not (figure 2 - which also shows clearly that there was no mechanical link between growth and inflation even in the 20thcentury). It seems unlikely that there would have been a visible Phillips curve then.

Click the image to enlarge

These were special circumstances. But in recent times, the liberalisation of trade (until now), with China joining the World Trade Organization in December 2001, and the opening up of a massive pool of hungry labour, can be seen as a supply windfall. Alongside it, another wave of technological innovation - in communications, digital media, automation, software, materials science, nanotechnology - has also delivered productive windfalls, as have improved industrial relations in some developed economies.

The technology gains may not have shown up fully in recorded output. Several official studies (such as the 2016 review of UK statistics chaired by Professor Sir Charles Bean) have suggested that digital or virtual output is simply not being recorded accurately. (How could it possibly be? A letter can be easily weighed and tracked, emails can't.) But when Robert Solow quipped in 1987 that “you can see computers everywhere except in the productivity statistics”, he may have missed the point. If output and productivity are being understated, maybe the new technology is showing up instead in the links between recorded output and inflation, and in healthy profit margins.

It is difficult to know for sure which side of the market - demand or supply - is in the driving seat. But at the very least, if we accept the possibility of supply-driven growth, we start to see the potential interaction of growth and inflation in a more open-minded way. In the possibilities shown in figure 3, the chances of being in the (favourable) bottom-right quadrant may be real.

Click the image to enlarge

And if the trade-off between growth and price stability looks friendlier than when viewed through our Keynesian, inflation-shaped spectacles, then central banks may well be able to ease policy, even while unemployment is still low, without doing too much damage.

There is still the question of whether an improved growth/inflation mix is already priced in to money and bond markets. A careful discussion of the 'right' level of interest rates needs more space than we have here, but we can note that as with the inflation/output trade-off, the link between interest rates and inflation has also been a relatively flexible one historically.

As with the Phillips curve, the link between, for example, nominal GDP growth and interest rates and bond yields seen in the last half century did not always work in earlier times. Interest rates often diverged from economic conditions, and not just briefly. Net of today's subdued inflation, current money and bond markets may not be quite as outlandishly expensive as they seem.

Meanwhile, back on the ranch…

What does this mean for investors? We should note quickly that keeping an overly wary eye on the inflation horizon has not stopped us advising positively on the last decade's markets. We have been too pessimistic on bonds, for sure, but stocks have (of course) been the big winner so far in the post-Global Financial Crisis world.

Some analysts suggested that inflation would stay subdued all along. But they usually tended to argue from that Keynesian viewpoint. Their diagnosis was weakening demand, not strengthening supply, and they tended to be far too pessimistic on corporate profits as a result.

For business, the disinflationary world has not brought the predicted 'Ice Age', or aggregate loss of 'pricing power' - rather the opposite. US operating margins have hit new highs, even as inflation has stayed subdued, and the trend in developed world profitability (return on equity, adjusted for inflation) has hit 50-year highs.

Perhaps this is the most important investment insight from the possibility of supply-led growth. Low inflation and interest rates are obviously good for government bonds - but they need not be bad for business either.

Admittedly, for much of 2019, stocks' likely cyclical headroom has seemed to us to be falling as markets rallied - at least, on a conventional view in which inflationary excess and monetary penance lurked around the corner.

The jury is still out. It could be that central banks are indeed anticipating a horrible second half for growth, and that the thoughts of lower interest rates that they are so clearly entertaining reflect not a changed view of the growth/inflation link, but a more conventional cyclical insurance policy.

And we are not quite ready to jettison completely our inflation wariness. We suspect that if demand-pull inflation is still a risk, it is one that cannot be fine-tuned, and we'd rather see the central banks wait until the evidence - whether of recession, or of supply-driven growth - is clearer. Indeed, if Mr Trump is not careful, his lack of trade tact may yet kill the goose that helped lay the supply-side egg.

But perhaps we need to keep a more open mind. Today's bond prices may be more sustainable - and the implicit portfolio protection that bonds provide may be less expensive - than we'd thought.

Click here to continue: Market Perspective - Growth insurance - or inflation pass? Economy and markets: background

In this Market Perspective:

- Foreword

- Growth insurance - or inflation pass? (current page)

- Economy and markets: background

- Important information

Download the full Market Perspective in PDF format (PDF 3.92MB)

Listen to the latest Market Perspective podcast